So here’s the thing,

I was a little startled late last week to realise that the

Oscars were coming up this Monday. Time had completely slipped by me, and I had

barely written any of my usual post commenting on the Best Picture nominees. I’d

given a decent first-draft write-up on a couple of films, but for most of them

all I had were a few scraps and the odd half-formed paragraph here and there.

(This was particularly annoying, since I had seen all of the films a couple of

weeks ago so, unlike most years where there’s usually a film released just

before the ceremony, I really have had plenty of time to prepare my post.) So,

after a lot of effort, here is my last-minute post on this year’s eight

nominees. I feel less satisfied than usual with this post, with many films I

feel there is a lot more that I could have said but didn’t have the time to

articulate my thoughts, and I certainly feel that my transitions between ideas

could use a lot more work, but sadly I don’t have time for it. Nevertheless,

here it is.

[After the jump, comments on The

Revenant, Spotlight, Mad Max: Fury

Road, Room, The Big Short,

Brooklyn, The Martian, and

Bridge of Spies.]

This is a year where the big award is fairly up in the air;

no-one is really sure what will win on the night. That said, the film that has

the biggest buzz around it is probably The Revenant.

Leonardo DiCaprio plays Hugh Glass, a hunter and guide on an expedition with a

group of fur trappers who is brutally mauled by a grizzly bear. Glass is close

to death and too difficult to carry, so the expedition leaves Glass in the

hands of an old hand hunter called Fitzgerald, as well as Glass’s son and

another young man called Bridger. The three are tasked with waiting until Glass

dies, and then giving him a decent burial before returning. But Fitzgerald is

impatient and understandably concerned about danger to their own lives, so he

tries to hurry along Glass’s death; Glass’s son intervenes to stop the murder

and is himself killed; Fitzgerald then convinces Bridger that the son has

vanished, that there are Native Americans nearby, and they need to abandon

Glass. But Glass doesn’t die, and over the film we see him recover, survive,

and make his way to civilisation, motivated by his need for revenge against

Fitzgerald for the death of his son.

Much of the attention around the film has been on the

suffering around the making of the film; indeed, I’ve heard the film shoot

compared to the legendarily nightmarish shoot on Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo.

It was filmed in areas so remote that half-a-day was lost just in travelling,

in freezing locations where hypothermia was a constant risk. And meanwhile DiCaprio had to plunge into freezing cold water, eat an actual raw bison liver or

an actual (possibly still living) fish, or crawl naked into an animal carcass

in a snow-covered environment. And understandably the extreme nature of the

shoot has been the focus of the much of the media around the film. But I am

bothered by it. DiCaprio has basically been anointed as the inevitable winner

of the Best Actor award, and, fine; he’s an excellent actor, it seems wrong

that he hasn’t already got an Oscar, and this is a good performance from him.

But this is absolutely a make-good award, trying to apologise for never having

acknowledged him previously. Giving the Oscar to him for this film is just the

most extreme version of awarding people who punish themselves for their art,

just like those awards given to actors where the most significant part of their

performance is the amount of weight they gained or lost for the role; it’s

awarding the physical efforts of the actor prior to or in making without ever

considering whether what the actor did with that efforts is truly award-worthy.

Leonardo is good in this film, he’s not necessarily undeserving, but it does

always bother me when outside factors are taken into account when choosing the

winners, rather than simply considering the work on the screen.

The film was directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu, who

won the Best Director last year for Birdman, which I really liked.

Birdman had an underlying premise of presenting the entire

story as though it were filmed as one single shot, and I thought that had been

a brilliant idea, giving the film a disorienting drifting dream-like feel that

was perfect for that film in communicating the depression that our lead

character is dealing with. The Revenant is not a single shot

film, but it does embrace the idea of using a large number of long takes, with

the camera observing as the action plays out over several minutes. And on the

whole, it’s generally well-done, but it does feel terribly show-offy in a way

that often didn’t work for me. I found myself very aware of the filmmaking,

even distracted by it. Compare it to a film like Creed,

which had a boxing match that was all shot as a single take, and I didn’t

notice the fact until I read about it afterwards, because I was so caught up in

the moment that the filmmaking became almost invisible. Here, not only was I

frequently aware of the filmmaking, but there were times when I was bothered by

filmmaking choices. For instance, look at the bear mauling, which plays out as almost

one long take. We watch Glass walking around the forest, come across the bear,

it brutally attacks him for a while, then wanders off some distance, allowing

Glass to get his gun and shoot the bear when it returns, but that just makes

the bear angrier and maul him some more, until eventually it walks off, and we

end on DiCaprio’s face. Cut to a shot of the bear, which then runs up, grabs

Glass, and drags him off the edge of a small cliff, where the bear dies and

Glass lies barely alive. Now, as I was watching the film, I found myself

distracted by that choice; why present almost all of the mauling as a single

shot (a choice which was very effective in making the audience feel trapped in

the middle of this attack), but then cut to a second shot for the last 15

seconds of the attack. I don’t imagine there is any technical reason why they

couldn’t have finished out the scene in the same shot, but I have no idea what

creative reasons lie behind the decision. And these are the thoughts I had as I

was watching the film. There is a problem if I’m watching a scene as impressive

as that mauling scene but find myself thinking about the editing of the film.

And there were multiple times where this happened, where I realised I didn’t

understand why Iñárritu cut at that moment when a better cut could have been 10

seconds earlier or 15 seconds later.

As the poster proudly proclaims, the film is based on a true

story; Hugh Glass was a real person who really was mauled by a bear and left

for dead by a real Fitzgerald, and he really did manage to make his way across

incredible distances to his outpost. I’ve read a couple of short articles about

the incident [EDIT: There's a really interesting article comparing the movie and reality here.], and it seems like it’s truly an incredible story. But the problem

is that the filmmakers didn’t seem to have any faith in the story, and seemed

to feel the need to amplify the story. So it’s not enough that he overcame

these incredible obstacles to survive, it’s not enough that this be a tale of

the extraordinary capacity of the human spirit to survive; no, they need to add

to his achievements, until the entire thing feels fake. So at one point he

literally rides his horse off a massive cliff, but manages to survive because

he is lucky enough to choose the exact point where there is a similarly-massive

tree right by the cliff, allowing him to crash through the branches, slowing his

fall, and ensuring his survival. He didn’t know the tree was there, to me it

looked like it would not be visible from where he was, but yet he managed to luck

his way to the one place that would allow him to survive this impossible fall.

And then he’s able to cut open his dead horse and survive a cold night inside

its body, tauntaun-style. And that annoys me. When a film is being sold as a

true story, it’s a problem if the film adds so much to the story that is stops

being believable.

Or here’s another thing I’m bothered by: in reality, Fitzgerald

never killed Glass’s son, because Glass didn’t have a son. The only thing

Fitzgerald did was abandon Glass. I know that it’s common for “true story”

films to invent and change things around, but it still does bother me when they

go as extreme as making an actual person into a murderer in order to “tell a

good story”. Indeed, this feeds into another big problem I have with the

entirety of the film’s final act [spoilers follow in the rest of this

paragraph]. The film had been going for about two hours when Glass finally

arrived back at his home outpost. Fitzgerald, knowing that his crimes are about

to be revealed, flees, so Glass teams up with the outpost’s captain to track

down Fitzgerald, a sequence that drags out the film length by an extra

half-hour or so. And as I was watching this, I realised this wasn’t the film

that I had been watching. This felt very much like a sequence tagged onto the

end of the film to give it a more-action-packed ending. And apparently it was;

brief research reveals that the real Glass had forgiven Fitzgerald for

abandoning him (although there may have been factors motivating that decision).

So this entire climax was exactly as much of a contrivance as I had thought it

was at the time I saw the film. The film could have, should have, ended with

Glass returning to civilisation; that would have been a satisfying and triumphant

ending to the story. But because they had had Fitzgerald go so far as to murder

Glass’s son, having Glass just instantly forgive Fitzgerald was now impossible,

so they had to add this entire extended fourth act that didn’t work. Then, at

the very end, the film cheats completely; it allows Glass to decide not to kill

Fitzgerald, to choose the “better path” over taking revenge, while putting him

in a place where he makes that choice with an almost absolute certainty that

Fitzgerald will die within a minute in any case. It’s much easier to decide not

to seek revenge if you know the guy’s going to be killed any second now anyway.

And ultimately, it just bothers me that the film has been so

praised. I really don’t think it deserves the plaudits that it has been

receiving. It’s a good film, better than most films in any year, but it’s not the

great transcendent piece of cinema people are talking about. My big fear is, if

The Revenant wins Best Picture, then Iñárritu is likely to

win Best Director. To my knowledge, no person has won the directing Oscar two

years in a row. The notion that the first person in 65 years to take back-to-back directing

Oscars might be Iñárritu, admittedly a skilled director but a man who does make

seriously flawed films, troubles me. [EDIT: So it turns out my source for that information was incorrect. Two people have won back-to-back directing Oscars; John Ford and Joseph Mankiewicz. It has, however, been 65 years since it last happened.]

Far and away the best of the nominated films would have to

be Spotlight, the Tom McCarthy film about the small group of

investigative reporters at the Boston Globe who in 2002 wrote a series of stories

exposing a practice of systemic cover-up of child sexual abuse by Roman

Catholic priests in the Boston area.

I’m a big admirer of McCarthy. His first three films – The

Station Agent, The Visitor, and Win

Win – were each great little character dramas. I was a bit

disconcerted when he went to make a movie with Adam Sandler, but I was hoping

that film would be good; after all, Sandler has done some great work when he’s

worked with established directors outside of his usual indulgent bubble. Unfortunately

the general reception of The Cobbler, particularly from

people I trust who admired McCarthy’s earlier work, was so bad and so

bewildered that someone like McCarthy would make the film that I couldn’t bring

myself to watch it. Fortunately, it seems that film was a minor diversion

before he produced his best work in Spotlight.

One of the things that I really appreciated about the film

was that McCarthy had a very clear, straight line of focus in making the film. It

could have been easy to focus too much on the actual abuse, something that

would very quickly have made the story overly sensational, utterly unbearable,

or both. Instead, McCarthy keeps us at a distance from the events being

reported; we’re with the reporters as they conduct their research and the story

develops. And in that context, scenes of people studying old paper clippings,

drawing red circles around names in directories, become surprisingly gripping, and

we’re shocked as every new detail is uncovered. It’s a film that is fascinated

with the process of investigative journalism, with how you go about preparing a

story of this type. And as more details of the story are revealed , it brings

out great conflicts in the reporters about how and when to report this story,

and the ethical implications of that choice. In one of my favourite sequences

in the film one of the reporters discovers information about a neighbouring

house being used by the church as a place to keep paedophile priests, and

suddenly the importance of this story is all too personal. But what is the

ethical response to that information as a reporter? Do you alert the neighbours

to the risk posed by the people in that house, and in so doing damage your

chances of fully revealing the true story, or do you focus on the need to fully

report the story and expose those people who should have stopped abuse from

occurring but risk your kids and your neighbours’ kids becoming victims

themselves in the meantime? It’s a situation where there is no good solution,

and I loved that the film took the time to explore that.

One thing I was quite surprised by was how light-handed

McCarthy was in discussing the decline of the newspaper industry. After all, as

an actor McCarthy famously played Scott Templeton, the primary harbinger of

doom for the newspaper industry in season 5 of The Wire, and

I think I was half-expecting that to carry into this film. And the film

certainly touches on the decline of the industry and its causes (an early scene

has Michael Keaton, as the head of the Spotlight team, meeting with the new

editor, and it does seem entirely possible that in a time of the internet and tightening

budgets for media the team might be seen as being too expensive given the small

number of stories they write). But the film avoided explicitly commenting on

how far newspapers have fallen, instead telling this story as a celebration of

what newspapers could be. We live in an era of quickly written, poorly

researched, mistake-filled articles thrown onto the internet as quickly as

possible, often filled with comments from random people on Twitter as a way of

quickly adding to the article word count, so it was nice to see this as a

reminder of how important the work of the media really could be.

I was also impressed with how careful the film was in

avoiding becoming a typical diatribe about how awful the Catholic church is for

allowing these things to happen. Yes, it was terrible, awful that the church

knew about these events and covered them over, but it’s also clear that there’s

plenty of guilt to go around. The film almost suggests that the entire culture

in Boston is responsible for allowing the abuse to happen in that city, even if

only by inaction. The police let priests walk out without charge, while the

justice system is used to reach settlements that keep information about the

abuse out of the public eye. Even the news media is indicted; the Spotlight

team may be the heroes of the film for doing the hard work to expose this

story, but one of our main characters is revealed to have been given

information about abuses half a decade earlier but chose not to follow it up,

while when the idea of covering this story is first raised, this team of

investigative reporters actually dismisses the idea because you just don’t go

after the church. It’s only because of the insistence of the new editor, who

has new to Boston and who is not so ingrained in the culture of the city, that

the team even considers looking into the story; previously it would never have even

occurred to them to report this story. The message is clear: whether by action

or inaction, everyone was responsible for creating an environment where this

abuse was able to happen, which then raises the obvious question: what sins,

what evils, what abuses are there that we the audience have allowed ourselves

to not see?

The film also adopts an interesting view of the effects of

this cover-up on its victims. Obviously the children are the primary victims.

Fortunately the film keeps us away from much of the initial aftermath of the

abuse; that would be too tough. The voices of the victims are represented

instead by adult survivors who are able to show us how years, decades after

these crimes these people are struggling to rebuild their lives and come to

terms with what happened. But much as the film suggests that everyone bears

some responsibility for allowing an environment where these abuses can occur,

it also suggests that we’re all victims. Whether it be the devout Catholic

whose faith is damaged by the realisation of the horrors the church allowed, or

the people who have to deal with their own guilt in not taking action to stop

the abuses when they could have, there’s a degree to which we have all been made

victims by these institutions. (Wow, this really does sound like The

Wire.) Even the priests who committed these crimes are victims of the

cover-up. We only get one scene with a priest who is guilty of abuse, and

there’s an interesting choice made to not present him as a villain or some

hateful figure; instead he’s sad, confused, and we’re left dumbstruck at how he

explains his actions. It’s clear that by trying to keep this scandal under the

carpet the church prevented these people from coming to an understanding of

what they actually did, to the point where they weirdly become victims of the system.

I also appreciated how understated the performances are. This is a film where people do their work quietly, behind the scenes, where their key interactions are conversations held in confidence, creating a comforting environment where people can tell their stories. So even though the film is filled with great stars and much-admired character actors (people like Michael Keaton, Liev Schreiber, John Slattery, Stanley Tucci, Jamey Sheridan, Billy Crudup, even Richard Jenkins in a pivotal but uncredited voice role) giving incredible performances, there’s almost an anonymity to their performances. I loved everything that Schreiber, Tucci, or Crudup did in the film, but it’s easy to understand why they have been largely overlooked. Mark Ruffalo is the one person in the film that gets more of the traditional big moments that tend to be recognised as “great acting”; he tends to be the person running to the courthouse to get last minute information. And indeed, he’s at the centre of the film’s one moment of heightened conflict, where he is given the type of angry monologue that is sure to be played during the Oscar ceremony. But it’s a moment that comes naturally, arising out of a moment of genuine frustration and fundamental differences; both people want the exact same thing, they want to expose this terrible scandal, but do they have enough material to report the story now, or do they take another few months investigate the story fully but risk further abuse in the meantime? It’s a horrible position for the characters to be in, and the heightened conflict in that moment is completely natural. That said, it is also a big obvious acting moment which, as soon as you see it, you know will play as Ruffalo’s acting clip in the Oscar ceremony. To me, the best moment of acting in the film was by Rachel McAdams, yet I was surprised when she was given a nomination, since as great as she is, the role doesn’t offer the kind of flash that the Academy normally responds to. Instead McAdams’ highlight scene is a beautiful, small, subtle moment; it literally involves watching her sit wordlessly while someone else silently reads. It’s a scene and a powerful performance that has stayed with me for the past few weeks, but it’s a surprise that the Academy would acknowledge it over other bigger performances.

Historically, there has tended to be a strong correlation

between the film that wins Best Picture and Best Director. Now, in this case, Spotlight

may be the film that should win Best Picture, but I don’t know that it should

get Best Director. Tom McCarthy is a talented director, and someone whose work

I admire, but to me the directing in Spotlight was deliberately

invisible. He told the story, he told the story well, but it seemed to me that

he tried to make his directorial voice as invisible as possible to allow the

story to take prominence. To the degree that McCarthy deserves praise for the

film (and he does), it’s for his work as screenwriter in shaping the material,

not necessarily his directorial efforts.

To me, the best directed film of the year has to be Mad

Max: Fury Road, the most improbable film to be nominated for the Best

Picture Oscar this year (hell, possibly the most improbable film to get a

Picture nomination in the history of the Oscars). To see how insane it is that

this film has been nominated, just consider the premise: in a post-apocalyptic

desert wasteland, a one-armed female warrior helps a group of sex slaves escape

from a boil-covered warlord cult-leader, who sends an army of white-painted

followers in high-powered cars and monster trucks after the escapees; one of

the followers takes the titular Max along with him as a living blood bag so he

can receive a blood transfusion while on the chase.

This is a film that is nominated for the Best Picture Oscar.

Here’s how insane the film is: there’s a character in the

film called the People Eater. He has a metal false nose, his feet are so

swollen by gout as to be unrecognisable as limbs, and he has cut two holes in

his suit so he can string a chain between his nipple clamps. And I had

completely forgotten this person even existed in the film until I rewatched it

recently. In any other film, the

audience would be fascinated by this bizarre character; here, he just blends

into the scenery, just one of the multitude of freaks on display; instead everyone

just wants to talk about the Doof Warrior, a blind albino mutant who wears a

leathered human face as a mask and who plays a flame-throwing electric guitar

while riding a colossal vehicle carrying four people playing massive war drums.

I repeat, this is a film that the Academy thought was one of

the best of the year. Now to be clear, I do not say that to criticise. They’re

right; the film is absolutely incredible, positively experimental in its

exploration of the potential of the action genre. But I’m genuinely surprised

(and pleased) to find that the Academy, a notoriously conservative critical

body, can recognise the quality of this bizarre piece of art.

So why do I think George Miller, returning to the world of Mad

Max 30 years after the last film, deserves the Best Director Oscar?

Quite simply, I don’t think there has been another film this year that has been

more the voice of the director than this one. There’s an interesting video where the

director of photography discusses shooting the film and explains that George

Miller was very clear in wanting the key piece of information in any frame to

sit in the very centre of the image. Centre-framing an image breaks the rule of thirds,

one of the most fundamental rules of image composition. Normally you would only

centre-frame the image where the symmetry of the image was the specific point

of the framing (see for instance every Wes Anderson film). That’s not

the case here. Instead, during shooting Miller had a very clear vision for

exactly what the film would look like in its final form, not just visually but

in how it would be edited, and how the audience would react to the filmmaking.

This meant that he knew that the on-screen image had to be centred, not for any

image-composition reason, but because with his editing style and the insanely

busy images in the film a conventional compositional style would leave the

audience searching to figure out what to look at after every cut. Shooting with

the key focus in the centre of the image allows the audience to know to zero in

on one point on the screen and stay there for the entire film. In other words,

when making the movie, the entire shooting style was set by the anticipated eye

movement of the eventual audience. I genuinely find it fascinating that Miller

had such a clear vision for the film that he had thought through and understood

how every element of the film would affect the audience, and let that guide his

filming style.

And there’s an incredible amount of inventive action in this

film, moments where Miller will show us things that we’ve never seen. And it’s not just about some new spectacular

stunt or action beat, this isn’t some Fast and Furious film

where the focus is just on achieving something never before done. Miller’s

focus always seems to be on ensuring that the images we’re watching aren’t only

interesting on a “how did they do that” level, but that they need to have a

beauty and an interest as images in their own right. It doesn’t matter whether

we’re looking at the face of a beautiful woman, a vast desert canyon, or a car

exploding into shards of metal, Miller finds beauty in every element of the

film. For instance, the climax of the film features characters on long poles

swinging between vehicles, and it’s a genuinely original stunt sequence that I

don’t think I’ve ever seen. And Miller uses it in inventive ways; it’s not just

a cool way for people to move between vehicles, it’s a way to heighten the

tension because there’s always a possibility that people could swoop in out of

nowhere and grab our heroes, and there’s even a great moment where we find

ourselves on top of the pole swaying from side to side. But because Miller’s

eye is always primarily focused how this will look on screen, there’s a

constant visual splendour to the image. There are moments where we’re watching

these figures swinging, and there’s a grace and a beauty to the way the poles

flex and bend as the people move from vehicle to vehicle. It’s like watching a

great acrobat performing; we’re not just impressed by the technical achievement

that we’re watching, but we’re in awe at how effortless it all appears and how magnificent

it looks.

The other thing that is surprising about Fury

Road is how, for all its excesses and over-the-top vision, the film

is incredibly stripped down. In the entire film, there are maybe 20 minutes of

non-action sequences, moments where the film actually stops to allow people to

just talk. The whole film is effectively one big extended action sequence,

where the story is told entirely through action. It almost becomes

experimental, as though Miller is trying to find a new way to use action beats

as a storytelling medium. And it works. Admittedly,

it’s helped by the stripped-down nature of the story; for all the bizarre grotesqueries

on display, the actual story is very basic: woman rescues girls, villain wants

girls back, chase ensues. But within that framework, Miller uses the action in

the film to discuss its core themes and to explore its characters, its world.

For example, one of my favourite scenes in the film is a

moment where Furiosa needs to shoot an approaching vehicle, but she only has

one bullet. She grabs Max, tells him to stand absolutely still, rests the end

of the gun on his shoulder, and uses his body to keep the gun steady as she

aims and fires. Watching the film, I reflected how many other films would have

a line of dialogue about how she needs Max’s help since she only has one arm

and cannot use her other arm to hold the weapon steady. But the film never does

that, because Furiosa would never acknowledge weakness; instead the film relies

on the audience having been engaged by the film and therefore understanding why

she needs to use Max’s shoulder. And the scene becomes a great character

moment; it’s nearly wordless, but in this brief moment you see these

characters, who had previously been distrusting of each other, soften and

realise they can rely on each other. It therefore becomes this pivotal moment

where the character dynamics credibly and understandably shift, but it takes

place in the context of a big suspenseful action sequence that features barely

any dialogue.

That’s the reason why I’m actually a little worried by the

potential influence that Fury Road might have on action

cinema. I have horrible visions of films inspired by Fury

Road trying to adopt the same constant-action-sequence approach

without recognising that it only works here because the movie plotting was

stripped to its basics and the focus was placed on building the characters.

Many action movies these days seem to abandon strong character focus in favour

of tedious plotting where we have to do this before doing that in order to find

the AllSpark which will allow us to stop them, and it just would not work with

a Fury Road film style. I hope I’m wrong, but I fear that we

may be in for a period of incoherent non-stop action spectaculars that fail to

understand how Fury Road worked (much in the same way that

the Bourne films led to a decade of shakycam films that didn’t work nearly as

well).

I am reluctant to say too much about Room,

the most subtle and devastating of the nominated movies. The film opens on the

fifth birthday of Jack, a young boy with boundless energy and excitement for

the world of Room that he knows every inch of. And then his mother decides that

he’s now old enough to understand the truth about their world: that she was

kidnapped as a teenager and has been held captive for seven years, that outside

Room is not Outer Space but a world filled with people just like the ones he

sees on TV, and that Old Nick who brings their food is a bad man. And that’s

really all there is to say. The film certainly develops from there, going in

directions both expected and surprising (occasionally at the same time), but to

elaborate on how it develops would affect the impact of this compelling

character study.

I genuinely do not understand how you begin to make this

film. The entire film is told from the point of view of a five-year-old child

trying to deal with the discovery that his entire understanding of the world

has been utterly false, trying to grasp the fact that he is a prisoner who has

never known anything outside of his prison, unable to comprehend even the

fundamental fact that the whole world is bigger than a few metres large. I

don’t know how you even begin preparing for this film knowing that you are so

reliant on a young child to make the movie work. How do you find a child able to communicate

the weight of all this? How do you get a child to work with this material

without severely harming him? Is the child actually a good actor? Or is it just

a feat of remarkable direction and editing that they were able to bring

together the pieces and construct an incredible performance? Whatever it was

that put this on screen, the fact is that this film contains one of the most

impressive child performances ever; I struggle to think of a performance this

good from a child this young. Whether trying to comprehend the

incomprehensible, or being a typical child complaining that he can’t have what

he wants and not understanding why that’s impossible, or finding the strength

to help his mother when she is completely beaten down, eight year old Jacob

Tremblay just anchors the film with a convincing and honest performance. It’s

extraordinary to watch.

Equally great is Brie Larsen. One of the things I loved

about her character is that there’s a fundamental contradiction to her: because

she had to raise and protect her son she’s become much more mature than most

people her age, yet at the same time because she was taken as a teenager and

has been completely isolated ever since she’s emotionally still a teenager. It

gives her a huge range to play with the character, and she seems to really

relish the layers she gets to work with. Her need to protect her son paired

with the necessity to put her son at risk, the conflict that comes from having

learned to suppress her natural fury at the monster that has her, the

desperation of needing to do something, anything to escape coupled with the

knowledge that the wrong thing could get her and her son killed. She has this

incredible moment late in the film where she starts to question herself, ask

herself whether there were things that she could have done for her son to

protect him, whether her efforts to raise and protect her son were actually

selfish, and there’s genuine pain and heartbreak in the performance, held down

because she cannot risk breaking down at that moment. It’s possibly the most brutal,

emotionally devastating film moment I saw all year, played out over Larsen’s

face. It’s a smart, thoughtful,

compelling performance, and if the predictions hold true and she wins the Best

Actress award, it will be well deserved.

Lenny Abramson was nominated for Best Director, and he

absolutely deserves it. The challenge of making the film is that it’s told from

the point of view of this young child, and it’s almost impossible for us as

people who exist and live in the world to comprehend how it would feel to live

in this tiny constrained place. So Abrahamson has to help us see the world, see

the room, as Jack sees it. It’s remarkable how he does it. The entire room was

built as a 10 foot by 10 foot practical set, with removable wall panels so that

the camera could look into the enclosed space. (Apparently they had a rule

that, while the bulk of the camera might be situated outside the set, the

camera lens that determines what we see would always be within the actual

living space, preventing the film from cheating the size of the room.) Having

constructed this set, he then shoots it, not as though it’s a single location,

but as though it’s half a dozen locations. He shoots the kitchen as though it were

different to the wardrobe; the bathroom as separate from the bedroom. As a

result you ever quite get the sense of how the room is actually laid out, how

the different pieces relate. Which means that it feels as though there could be

some vast expanse between this area and that area. Of course, we know

intellectually how confined the characters are; the film never hides that from

us, including in one scene where Jack is exercising, running from wall to wall,

a distance that he can cover in a few steps. But it never feels confined to the

audience, which is as it should be. Because Jack doesn’t know how tiny his

world is, Abrahamson keeps us away from understanding just how small their

living area actually is. I suspect many directors would give too much weight to

the constraints that come with this living condition, reminding us how tiny the

room is, but Abrahamson’s approach shows a clear understanding of the material

and how to make it work cinematically. It’s impressive work from a director

I’ve been meaning to look into for some time.

When making The Big Short, co-writer and

director Adam McKay set himself a big challenge. The film is about a group of

people in the mid-2000s who realised that there was a massive housing bubble,

that a number of financial instruments created by the major banking

institutions had both amplified that bubble and fixed a date where it would

inevitably burst, and that this would lead to the worst financial crisis since

the Great Depression. And so, at a point where no-one else can see the problem,

these people started putting in place investments that would allow them to make

money out of the crisis, in effect betting against the US economy.

So there’s the challenge. This is a film that looks at a big

important issue, one with effects that still echo today, but to grasp what’s

going on you need an understanding of boring-sounding financial instruments so

complicated that even the people who created them may not have fully understood

what they were doing. You’ve got to understand how all of these different

elements and instruments interacted with each other. And you’ve got to communicate this

information in a way that is interesting and engaging to the general audience.

And even if you do that, there’s an issue of moral complexity to the story; the

entire world economy tanked, millions of people lost their homes, their jobs,

and this is the story of the people who were able to take advantage of this and

who made lots of money out of this event, so can you or should you avoid making

heroes out of these people?

In approaching this film and facing these challenges, McKay

had a big advantage: he has a solid comedy background. I think this allowed him to be very sensitive

to the response of the audience and how to focus on entertaining the audience.

I’ve seen people call it a comedy; I don’t think it really is (it’s not as

funny as that term would suggest, although it is amusing). But at every point

in the film, McKay makes the choice that will be most interesting to the

audience. As a result, a film that could be dry and complicated and lecturey

instead becomes light-hearted and enjoyable. He adopts a self-aware shooting

style, where characters break the fourth wall and address the audience to

provide key information, or where the film cuts away to different celebrities

outside of the film to provide a plain English explanation. The big advantage

of this approach was that it allowed the film to avoid common movie clichés,

which in turn strengthened the film. Often movies will resort to having

incredibly smart characters ask for something to be explained to them as though

they’re five years old, even though they should already understand that thing,

in order that the audience can hear the explanation. But that always undercuts

the characters, because suddenly that person seems incompetent or stupid. However, in this film the characters always

understand what’s happening or what they’re talking about (unless their lack of

understanding is the point of the scene), and instead we get cutaways to

Anthony Bourdain making a stew or Selena Gomez playing blackjack while

explaining how these activities are analogous to what we’re watching. Suddenly,

we the audience clearly understand what’s happening, and the film’s characters

still appear smart, because they’ve always known what we’ve just been told.

(Admittedly, not all of those cutaways work. The first time the device is used,

we find Margot Robbie in a bubble bath; her being in the bath bears no relation

to sub-prime mortgages, so that moment begins feeling rather leery in a way

that was uncomfortable. But for the most part, it works.)

Another thing I was impressed by was one early moment where

a contrived situation occurred to give characters information, and they stop

the film to explain “that’s not what actually happened, here’s what actually

happened, but it’s longer and more complicated and boring than what we’re

showing you.” It was open about moments where the film simplified and

fictionalised the true events for narrative convenience. That smart thing about

this is that it wins a lot of trust in the audience; unlike The Revenant,

which seemed to fictionalise the true story to such a degree that I questioned

the truth of almost everything that happened in the film, the fact that this

film was so open when it fudged the true events bought itself a lot of capital.

Suddenly we believe the film will be honest with us, so later on in the film

when an improbable over-the-top movie scene takes place, they have the ability

to tell us “this actually did happen” and we can trust them.

McKay’s other strength in making the film is the fact that

he is ANGRY at the fact that the financial crisis occurred, and he doesn’t

attempt to hide it. This means that, even though some of the characters are somewhat

sympathetic, McKay is able to keep the audience at a distance from them. We’re

always aware of the level of damage being inflicted on the world, and while the

film’s main characters may not have been responsible for causing the crisis,

these are people who made millions of dollars from the devastation that would

follow. As a result, whenever the characters begin to forget the reality of

what is about to come they are harshly and forcefully reminded what is actually

happening. McKay’s anger at the situation really only becomes intrusive at the

end, in an annoying postscript where we’re all told how all the people who were

responsible for the collapse were arrested and sent to jail, before McKay stops

and tells us that no, actually the people who caused it all to happen are still

in their same positions, are still making millions of dollars for themselves,

and, oh, are beginning to offer “new” financial instruments that look an awful

lot like the instruments that led to the crisis in the first place. I don’t

disagree with McKay’s anger over this matter, but it’s the one point where his

anger got in the way of entertainment; the bitter sarcastic tone of the

postscript never quite fits with the rest of the film. Still it’s a minor

blemish on an otherwise solid film. There are probably better films that could

have been nominated but weren’t, but I really did appreciate The Big

Short’s inventiveness in finding a way to make a truly entertaining

film revolving around collateralised debt obligations, so I’m pleased with its

nomination.

I was probably not in a good place when I went to see Brooklyn.

I’d rather ambitiously decided to walk down to a newly opened cinema to see the

film, which was a mistake; the walk itself (about 4km) was the length of my

regular walk, so should have been quite achievable, were it not for the fact

that it was the middle of the day on one of the hottest days of the summer. I

arrived at the cinema ten minutes before the screening, absolutely exhausted,

boiling like you wouldn’t believe, feet in pain from shoes that were not up to

a walk of that distance, and with the dawning realisation that I was going to

have to walk all the way home again in a couple of hours. All of which meant I

walked into Brooklyn focused on a million things other than

the film was about to see.

And then Brooklyn started, and I fell in

love with the film. Saoirse Ronan is just wonderful as Eilis, a young woman who

sees no opportunity or future in her small home town in Ireland, so jumps when

offered the chance to move to New York. And that’s basically the film; this

woman discovering a world she never dreamed of seeing, building her life,

finding opportunities to pursue her dreams, develop her career, and fall in

love. But primarily what I found myself caring most about was this story of a

young woman trying to find her identity; is she an Irish woman living in New

York, or a New Yorker who came from Ireland? And it’s that constant pull that

gives much of the film its power.

To me, the thing that I found particularly special about Brooklyn

was that it was fascinated by the immigrant experience, and how much the world

has changed in such a short time. Whether you live in the United States like Eilis,

or in New Zealand as I do, the fact is that these are countries that were founded

by immigrants; people who put aside their entire existence to move vast

distances to build a new life. And sure, we know that centuries ago travel between

countries would take weeks and months, but I loved the reminder that as

recently as 60 years ago the distances between countries were still massive

barriers. You might move to a new country, and build your life, fall in love,

get married, have children, and your family and friends, the people who are

closest to you, might never get to see your new life, might never get to meet

your new family and friends. To them, these people might simply a name in a

letter or a voice on the phone. People always talk about how the world has

changed, and it certainly has, but in an era of cheap air travel, social media,

and Skype, it’s remarkable to see how truly isolating it could be to move to

another country, even as recently as for people in my grandparent’s generation.

Early in the film, it’s commented that of course Eilis is going to live in

Brooklyn, since that’s where all the Irish immigrants go to live. And so we

understand how these strong cultural communities can build up in large cities,

because when you are so isolated from everything you’ve ever known there’s a

strong draw to anything that feels familiar.

So much of what I loved about Brooklyn is

just in the sheer power of its beauty. I can honestly say that I did not see a

more beautiful film than Brooklyn in the last 12 months. Indeed,

I was surprised to realise that the film didn’t even have a nomination for its

cinematography; there’s a richness to the film that I just found myself

constantly in awe of. And the costumes; ah, the costumes.

To be honest, I most likely might never have noticed the costumes were it not

for the fact that while walking to the cinema I was listening to a podcast

where one of the hosts referred to having seen the film and praising its use of

costumes. In particular, she had noted the unusual decision to reuse the

clothing; it’s normal in most films for characters to seemingly have a

limitless wardrobe, able to supply the perfect clothing for every scene, but

here a point is made that Eilis has limited clothing and has to rewear

everything. Having heard that comment, I did pay attention to the costumes, and

was struck by just how stunning the 50’s-style clothing truly was. I developed

a weird affection for her clothing choices; I like this outfit, that outfit

doesn’t quite work for me. There was even a point where she was making a decision

that I was disappointed by, and one of the things that I was particularly

bothered by was the fact that she was doing this while wearing this clothing

that had certain associations and memories attached to it that made her choice

feel particularly like a betrayal.

But for all its visual beauty, the film’s most powerful and

beautiful moment is found in a scene in a grey room with grey people, where

Eilis is simply an observer who gets forgotten about. The thing about Eilis is

that her story is a success story; we finish the film with a clear

understanding that Eilis has come through this crisis of identity, knows who

she is, and is in a place where we can be sure she’s going to be okay.

Obviously that wasn’t the case for all immigrants. Which is why the best scene

in the film takes place at a soup kitchen, where a group of men, no doubt all

of them having left Ireland filled with hope for a better life but whose dreams

were never realised, mournfully sing a traditional Irish song. And the film

just pauses to take in the scene. We’re told that these are the men who built

New York City, and we find ourselves reflecting on how much of our world today

may have been built on the efforts of people who might have been effectively

abandoned and forgotten. I appreciated the film pausing to give those

characters their moment of expression, longing for a home that they miss and

will never see again.

There has been an announcement that work is underway on a TV

spin-off starring Julie Walters reprising her role as Mrs Kehoe, the deeply

conservative owner of the boarding house where Eilis lives, and I find that

decision quite interesting. To be honest, I liked, but didn’t love, Walters’

performance. By itself it was a lot of fun, but her scenes were broader and had

a more specifically comedic tone than the gentle tone of much of the film,

which for me kept her scenes from feeling fully integrated into the film. But I

like the idea of doing a series with Walters, where Mrs Kehoe can set the tone

of the piece rather than having her seem at odds with the whole.

I think I’ll keep my comments on The

Martian fairly brief, since there’s a good likelihood that you’ll

have already seen, or at least familiar with, the film about an abandoned astronaut

trying to survive for years on Mars. (The film is, after all, the most

successful of this year’s nominees, was released several months ago, and was a

genuine blockbuster hit.)

The thing I really appreciated was that the film was smart,

and that it treated the audience as though they were smart. The original book

was known for exploring the actual science that would underlie a person’s

efforts to survive in those circumstances, and the film does a great job in

doing so as well. But it does so with careful consideration, understanding that

the audience watching the film is likely to have some basic knowledge of the

world. This meant that, in one moment when Mark Watney has to use hexadecimal

numbers to communicate they could rely on the audience understanding (or at

least figuring out) what was happening without explanation, and instead they

could focus their exposition on explaining the science behind making water on a

planet where there is none. There are a few moments where it does feel a little

too expository (one moment, where Watney holds a document that he wrote up to

the camera to prove that he’s a botanist, seems a little silly when you

remember that in the world of the film the only people who could ever see the video

will already know his background), but for the most part, the film approaches its

storytelling with care and thought. This

meant that I watched an entire film about a guy who survives for years on a

desolate planet, and the only time that I ever questioned the believability of

his survival was literally in the final few seconds before his rescue, when I

felt they pushed one step too far. But for the most part, this film seemed like

a genuine exploration of what it would take to survive in an alien environment,

and a celebration of the knowledge and understanding that could allow this to

be achieved. And it was so satisfying to watch a well-made intelligent blockbuster

approach its audience as thinking adults.

Ridley Scott is a great visual director, who has given us

some of the most distinctive filmic visions in cinema history. Here he’s doing

some strong work, and seems to really be enjoying playing with the idea of one

man set against the vastness of an entire planet. I managed to see the film in

3D, and while I doubt it would be anywhere near as effective on most home

setups, in cinema the use of 3D was truly impressive, emphasising the sense of

a planet that could go on forever, that is vast and threatening, that seems

impossible to traverse or to escape. It’s a fine reminder of just how strong Scott

can be, and some of his best work since 2000.

Unfortunately Scott can be a director whose ability to pick

projects that allow him to live up to his talent is not always strong. (Which

is how we get Robin Hood and Exodus: Gods and

Kings.) Fortunately, in The Martian, he had a

script by Drew Goddard. Goddard started his career writing episodes in the

final seasons of both Angel and Buffy, and

he later co-wrote the brilliant The Cabin In The Woods with Buffy

creator Joss Whedon (a film Goddard also directed). The world of vampire slayers

and zombie killers might seem miles away from a hard-science-based adventure, but

I do feel that Goddard’s work in the Whedonverse allowed Goddard to develop the

strengths he would need to write The Martian. After all, one

of the most distinctive marks of Whedon’s work is the careful balancing of

genuine humour to lighten the tone without ever undercutting the drama, and (as

the Golden Globes reminded us when they categorised the film incorrectly as a

comedy), The Martian has a strong sense of humour running

through the film that keeps the film light and fun and entertaining. Without

that tone, the film would have turn into simply a punishing survival story; it

would in effect have been The Revenant on Mars, and no one wants

that. Instead the film becomes a piece of pure entertainment, a thrilling film

where we’re not worried about whether or not Watney is going to die, but rather

we’re excited to see what he’s going to do to survive. It’s surprising how much

a few dumb jokes can change the entire tone of a film, but they really can.

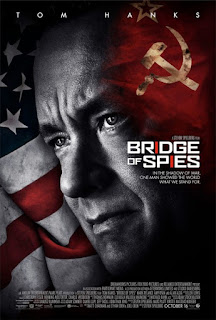

The film I’m most surprised to see in the list of nominees

would have to be Bridge of Spies. Which is not to say that

it’s a bad film; it’s a solid, well-made, entertaining example of

based-on-a-true-story cinema. I enjoyed the film, and if you’re interested in

the film it is worth seeing. But it’s by

no means “one of the best movies of the year”.

Based on a true story, Tom Hanks stars as lawyer James

Donovan, who is tasked with trying to defend Rudolf Abel, an older man charged

with having worked as a Soviet spy for decades. Donovan does his best to defend

Abel, and in so doing becomes one of the most hated people in America, but

ultimately is only able to save the man from execution. But not long after the

trial an American spy plane is lost and the pilot captured by the Soviets, and

Donovan finds himself travelling to East Germany to negotiate an exchange of

Abel for the pilot.

And in that summary, you can see a bit of the problem in the

film. There are really two stories in the film: the story of a lawyer whose

conscience forces him to provide the best defence possible for his client,

despite great pressure from people who want him to put in a token effort; and the

story of an ordinary man who find s himself inadvertently thrust into

international politics, trying to negotiate a settlement between two superpower

nations. Both of those are interesting stories. The problem is that the film is

clearly more interested in the second story, and treats the trial story as a

necessary evil, needed to establish why Donovan is even involved, but otherwise

something to be rushed through. And while I enjoyed that second half, I also

found the first half fascinating. There’s an inherent conflict in that story:

Donovan is specifically hired because it will look like they’re giving Abel the

best defence, but everyone is very clear that they don’t really want him to try

too hard, and the fact that he actually does try to win the case winds up

alienating him from his friends, his colleagues, and the general public. I

suspect one reason why the film rushes over that part of the story may be

because there’s not that much suspense in it; there’s never any doubt that Abel

will be found guilty, given that the entire premise of the film revolves around

a prisoner exchange. But stories can work even where the outcome is inevitable,

and the time spent with Hanks’ character, fighting with people who outwardly

present themselves as being concerned about the constitution but who privately

would look to dismiss it out of convenience, is genuinely gripping. So I can’t

help feeling disappointed that the film treated those early trial scenes merely

as a necessary setup for the film. It would have been better had they evenly

split the film, with the first half being the trial story where we get to know

the characters, and then leading into the more suspenseful second half story.

It might not have fit within a conventional three-act structure, but at least

it would not have felt like the film was skipping over some of the most

interesting material in the story.

The big mystery about the film is the involvement of the

Coen brothers. The film was originally pitched and written by Matt Charman,

with Joel and Ethan Coen coming in to work on later drafts, and I do not really

understand why. The Coens are some of our most distinctive filmmakers working

today, and it’s weird to see them working on a film that seems so unmemorable.

Other than the script possibly being slightly funnier than a film of this type

would normally be, there’s nothing to really distinguish this script as coming

from the Coens. It feels weirdly anonymous, and I do not understand why they

would want to do something so invisible.

Much of the attention around the film has been focussed on

Mark Rylance, playing the Russian spy Abel. And I can’t help feeling that the

praise has been a little overblown. It’s a good performance, enjoyable to

watch, and he does make the character genuinely likable, so that the formation

of the friendship between Abel and Donovan convinces, but it’s very restrained,

almost too much so. Abel never seems bothered by anything. He seems overly resigned to his fate, to the

point where he seems completely detached from the consequences of everything

that happens. He’ll discuss his own likely death with a shrug. And the film

makes a little running joke of his detachment; whenever someone suggests that

Abel should be worried about something or reacting differently to a

development, he always replies “Would it help?” Which is funny, although the

joke does get overplayed by the end. But

it reached a point where it stopped feeling like Abel was an actual person, and

he just became this cypher who seemed so disconnected from the film that it was

like his character had almost been pasted on top of the movie. Rylance was

certainly memorable and likable, but never really convinced me as a person who

existed.

I was, however, impressed with Tom Hanks. It’s not a

particularly revelatory performance, this isn’t Captain Phillips

or anything of that level, but I really enjoyed everything he brought to the

film. The film throws a massive barrier in our way when we first meet Donovan;

he’s working as an insurance lawyer, and we’re introduced to him arguing that

his client, an insurance company, shouldn’t have to make full payment on a claim

where the insured party hit five people with his car, on the basis that there

was only one accident involving five victims, rather than five separate

claimable incidents. And he makes the argument very well. There’s a degree to

which that choice risks alienating us from our hero right from the start;

there’s something fundamentally uncomfortable about being asked to side with

someone making that type of argument, and probably the only reason we still

kind of like Donovan at the end of the scene is because he’s Tom Hanks and

everyone loves Tom Hanks. But as the film goes on, it becomes clear why we were

given such an uncomfortable introduction to the character; it’s a defining

characteristic of the man that he will fight to his utmost ability to offer the

strongest argument he can find to achieve the best outcome for his clients,

regardless of our moral feelings about the clients, because that is his job and

he fundamentally believes in the right for everyone to have the best legal

counsel they can get. It’s demonstrated by his arguments during Abel’s trial

and sentencing, and crucially it’s demonstrated during the tense negotiations

in East Berlin, where Donovan finds himself playing off tensions between the

Soviets and the East Germans in order to improve the outcome for the US. I was

genuinely impressed with the way the film managed to take a man trying to help

an insurance company avoid paying its obligations and turned that behaviour

into a characteristic that deserved to be celebrated.

One of the big joys of the film was the sense of location,

the way the film takes you back to the early days after the building of the

Berlin wall. There’s a moment early on where one character just crosses from

West to East Germany while the wall is being built, jumping over the blocks

that mark the first level of the wall. It’s fascinating to see, to get the

sense that people didn’t really understand what was even happening. East and

West Germany had been divided for over a decade before the wall was

constructed, and so it’s interesting to watch and ponder how people would have

reacted. In an era where the two countries had been theoretically divided for

years without any practical separation, it must have been difficult to truly

understand the effect that building the wall would have had on the Soviet side,

and (from memory) most people in the film didn’t seem too bothered by the need

to leave before they became trapped. It’s really only once that country is

completely isolated that it becomes clear just how terrible the country would

become under isolation, and I was fascinated by this sense of oppression and

weariness in the country.

So it’s a fun film, with a lot of good points. But the simple

fact is, this film would probably have been forgotten had Spielberg not

directed the film. Now, Spielberg is a great director, but this is decidedly

average work from him, and while that still keeps it as one of the better films

of the year, it’s just not one of the best. And there are other films that

should have been nominated in its place. I haven’t yet seen Carol,

which was widely expected to be nominated, so I cannot comment in its

exclusion, but I do know that that I had been convinced that Inside

Out (possibly the best film ever made by Pixar) or Creed

(which managed to revive the Rocky franchise, make it

relevant, and return it to the emotionally honest heights of the first film)

would be nominated. I would also have loved to see The Hateful Eight

earn a nomination; I know a lot of people dislike that movie, but I thought it

was fascinating, both as an exploration of how much tension can build in a film

before release, and thematically in its examination of how we allow the stories

we believe to govern our behaviour. All

of these films could have deservedly been proclaimed one of the best movies of

the year, and it’s just a shame that they were overlooked in favour of a solid,

but generally unremarkable, film from a filmmaker who has done much better work.

No comments:

Post a Comment