So here's the thing,

As we get to the 2024 film festival in a couple of days, it's time I get around to posting my reflections on the films from the 2023 festival. Usual disclaimers - written in great haste shortly after the film, not a "review", just an attempt to capture my response and reflections, written primarily for myself to help me remember each film given the mass of movies I'll be seeing in a short space of time.

[Comments on the 39 films I saw during the 2023 film festival, after the jump]

Anatomy of a Fall

The film festival opened with this wonderfully understated courtroom drama, which won the Palme d'Or at Cannes earlier in the year. Sandra Hüller plays Sandra, a successful author in a strained marriage, with a young son who is vision-impaired after a tragic accident. One day, the son returns from a walk to find the body of his father, who died after falling from the attic window. Was it an accident? Was it suicide? Or was he pushed, in which case Sandra is the only possible suspect.

Much of the film takes place in the courtroom, in the heat of the trial, and I appreciated the way director Justine Triet deliberately held us at a remove in those scenes - we weren't participants, we were observers watching from a distance. And we are never privy to any real information beyond what we are given in the trial - we don't see the husband and wife together before he dies, and while we do see the two together in moments that visualise the evidence being given at the trial, we are certainly never witness to any moments that would clarify any ambiguity around the case, and so we are left to judge what we think happened with only the information the jury has. And there is a lot of ambiguity here - while the film is certainly on Sandra's side, there is enough uncertainty around this crime that it seems a genuine possibility that she may have committed murder. I also appreciated how devoid of histrionics the film was when compared to other films in this genre - there's no big "You can't handle the truth!" moment; just a bunch of professionals in a room trying to test and explore the evidence to come to their best conclusion. The climactic courtroom moment doesn't even take place in a packed courtroom, but instead in a near-empty room where the only people present are those with an actual court function. The film so downplays its courtroom drama elements that even the delivery of a verdict, the moment the entire film has been building up to, nearly slips by without notice. And I loved this more restrained tone from the film, particularly as it gave a sense of authenticity to the story in a way that really amplified the tension.

But that sparse tone that the film adopts during the trial sequences vanishes once we leave the courtroom. Gone are the restrained, distanced shots, replaced with hand-held close-ups. There's a noticeable intimacy to these moments - watching Sandra with her son or with her longtime-friend-turned-lawyer - as we come to see these people as they are. It really drives home the artifice of that courtroom setting, and the real challenge that comes with trying to judge a person in those moments.

Hüller is just fantastic here. She brings a sense to Sandra of a character who has been completely destroyed by this experience, but who feels she needs to hold back on her grief for the sake of her son and to present a brave face for the court. There's guilt in her performance, that she does feel that she did kill him, even if she didn't physically push him, through her contributions to the ugliness of the marriage, or her failure to support him even when she knew of his mental health issues and she saw signs of possible suicidal tendencies. And as the trial begins to delve into the nature of her relationship with her husband, you feel her growing demoralisation as she realises she is going to have to stand in court and confess to her lowest moments, the things she's most ashamed of in her life.

Milo Machado-Graner is similarly fantastic as Sandra's son Daniel. It's through him that we particularly explore the fallibility of memory as he adjusts his evidence about his incident, perhaps because he realises he's misremembering, or perhaps to help his mother. And in the film's most shocking moment he goes to extreme lengths to try to process some of the information his mother gave on the stand, with the eagerness of a child who hasn't yet quite learned to process the risk and permanence of his actions. But it's also fascinating to watch this world through this young child's view - we understand what he did and did not know about his parents and his father's struggles, but there is a lot that they rightfully kept hidden from him and, as the trial goes on, it was intriguing to see his struggles to deal with insights into his parents' relationship that no child should never have.

It's a fantastic, enthralling experience. At 2 1/2 hours, it's not short, but there's a real urgency to the filmmaking that drives it forward and that ensures that it always holds you in its grip. I just loved it.

In 2017, a woman named Reality Winner, an Air Force veteran now working as a translator for a military contractor, printed a copy of a confidential document and sent it to an online news provider. Several weeks later, she returned home from the shops to find a team of FBI agents with a search warrant to search her house, car, and person. The agents made an audio recording of their conversation with Reality during the search, and this docu-drama presents, in something close to real-time, the 104 minutes as the search takes place, with the dialogue taken entirely from the transcript of the audio recording.

The fascinating thing about this verbatim approach is the way it spends time on moments that would almost always be elided over. I've seen many movies with search warrants being executed, and I've never seen anything that spends this much time on taking care of the pet dog, or the current location of the pet cat, or how long it will be before she can put away her perishable groceries, or exactly what firearms she owns (complete with amusement at her pink assault rifle), or which room would be best for the agents to have a conversation with Reality, whether she wants to sit down, whether she wants a drink of water. But it's in all of these moments, and in the time that they take, that you can feel the tension build up, as the agents just leave Reality to sit and stew in her realisation where this is all going. The agents speaking to her feel friendly, nice, but you become very aware that every moment is part of the interrogation, is part of trying to put her into a mindset where she will confess to her actions.

I really did enjoy Sydney Sweeney in the title role. She brings a nice tension to the character as we observe the version she presents to the agents - honest, open, a little bit confused by whatever is going on, but eager to help - while all the time there's a tension behind her eyes as she tries to think of a way out of this situation, trying to bluff her way into safety, or hoping against hope that perhaps the FBI are not here about that, that perhaps if she holds back any kind of confession she may discover that they are here about some other situation, something that will not result in her spending years in prison. And it's devastating when she eventually does break down and confess, because you can feel her realisation that her life as she knows it has ended.

The film is for first-time director Tina Satter, who previously worked on adapting this material as a play on stage, so she brings a real familiarity and confidence with the material. But I was impressed with how strong her filmmaking instincts were. For the most part, it's very moderated, very much a just-the-facts presentation, but she does well in embedding the audience in Reality's increasing sense of isolation in her house filled with people, her sense of violation as her entire world is turned over. The moments where the film does get showy arise when the film has to grapple with the realities of the situation. If the transcript includes some redacted text, the characters will glitch out of reality for a second to highlight that fact - even when we know broadly what was being said, the focus on presenting just-the-facts means that it's better to highlight the absence of actual dialogue then to invent dialogue that is not exactly what was said. The film also frequently cuts to the actual transcript being dramatised, or even to relevant Instagram posts from the real Reality Winner, all ensuring that the audience never loses its understanding that this is just a dramatisation, but it's also as close as we can get to an accurate presentation of actual events.

My only real issue with the film comes from the way that the constraints placed on the film, well, constrain the film. Because the film is so focused on recreating the 104 minutes of this search, and exactly replicating what was said at that time, there's limited ability to really discuss the wider issue. There's no real way to explore the merits or otherwise of Reality's actions or what her motivations were in leaking the document - after all, the biggest explanation she gave at the time was irritation that her employer was always playing Fox News. Nor is there really any way to place her actions in the broader context, to ask whether she was right to release this information, or to explore any comparisons between the punishment given to her against that imposed on other people who committed comparable crimes. But while I would be interested to see a film that did engage more fully with her choice and her motivations for making that choice, by its nature this film can never be that film.

That said, it is an excellent and riveting film, and I would recommend it.

In Brazil, a family in poverty struggles to cope, making money as charcoal burners, with a side-line in chicken meals with blood gravy. But then one day, the nurse taking care of their bedridden, nearly comatose, grandfather offers them a solution to their money troubles - they just need to euthanise the grandfather, and this will make room for a drug lord on the run to come and hide out in their home for some period of time. But this experience does not go well for them, especially as the drug lord is frustrated by having to go from living in a massive mansion with absolute luxury to living in a run-down, cramped house with empty shampoo bottles and needing to snort cocaine off a child's plastic toy.

Hitchcock used to talk about something called "fridge logic". The idea essentially is that it's possible to have something in a film that doesn't really make sense, but as long as you don't notice this while you're watching the film, that's fine. If a few hours later as you walk to the fridge you find yourself thinking about the film and suddenly realise it had a logical flaw, that's not a problem because the film so captured your attention at the time that you didn't notice this flaw. However, if as you're watching the film you're thinking about how it doesn't really hold together, that's a problem with the film.

Unfortunately, that's where I was with Charcoal. There is such a massive leap from "we're having financial difficulties" to "let's kill grandfather" that I was baffled by how quickly the characters made the jump to that decision. And while crime lords may have a view that life is cheap, I struggled to comprehend how anyone could be confident that approaching a regular person with such a proposal would be successful. And how do you, as a regular person, make the jump to being okay with killing a family member? Then they make the decision to burn the grandfather's body in the charcoal furnaces - which just prompted me to wonder what the plan was going to be when the time came to publicly acknowledge the grandfather's death (a question the film tries to slide past in hope that it's not noticed - believe me, I noticed). And then you see how this arrangement will work, and you wonder why it was necessary to kill the grandfather in the first place - it's not like the drug lord is pretending to be the grandfather, and the drug lord is sleeping on a makeshift bed separate from where the grandfather was, so the only reason they needed to kill the grandfather seems to be to free up a (very soiled) mattress. And that seems unnecessary. Plus there's the fact that the characters, for the most part, don't really seem to be too conflicted about having ended the life of a family member - other than one scene, where the father drunkenly forces the family to celebrate the birthday of the dead grandfather, once he's dead the grandfather seems to fade from memory. Most of the tension in the story instead seems to come from the challenges of trying to hide this person in the home, whether it be from his chafing against the constraints of the house or a consequence of living in a small village where everyone seems to just casually wander into each other's home. And then there's the late film suggestion that this drug lord may not be the only person being hidden in this small village - all of which just started to strain credulity. And to be clear, these were not issues that occurred to me after the film - these were questions and problems I had while watching the film that were never answered.

The disappointing thing is that it is an enjoyable film. It retained my engagement throughout the film. There are some nice moments of laugh-out-loud black humour that lightened the experience. And I found the characters really rather sympathetic - surprisingly so, given the action these people take at the start of the film - and this speaks to how much the actors did work to bring something to the characters that we could connect with.

But unfortunately, I simply didn't feel that the film held together, and that was a real problem.

Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret.

Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret.

I've never read the original Judy Blume novel on which this is based. I'm obviously aware of its place as a modern classic for young adults, but being a boy growing up, the only Blume books it was socially acceptable for me to read were the Fudge novels, and there's no way I would ever have read anything about a girl's fearful approach to puberty. So I came to this film without any particular expectations or prior experience. And seen solely as a movie, the film was fantastic.

In 1970, 11-year-old Margaret is distressed to discover her family is moving from New York, away from her beloved grandmother, out to New Jersey. Once there, she falls in with a group of friends led by a proto-Mean-Girl named Nancy, who is obsessed with boys, increasing the size of her bust, and experiencing her first period. At the same time, her teacher suggests she undertake a research project that for the first time has her considering religion and trying to work out what exactly she believes in.

I can certainly see why this story would have such resonance for young girls. It feels like a very honest portrait of what that experience of growing up is like. As a boy, we get the lucky end of the puberty experience; girls have to go through much more extreme body changes, both visibly and intimate, and then as you develop you get more attention, not just from boys, but also from girls who gossip about you doing "hand stuff" just because you've developed breasts. And there's this weird tension as a young person where you want to grow up, you want to be seen as mature, as an adult, but at the same time it feels as though becoming an adult is genuinely terrifying. And the film is extremely effective in portraying and exploring the challenge of that experience. There's also the weird up and down of emotions that kids develop as they approach puberty, where they seemingly leap from highs to lows in an instant, where everything feels as though the world is collapsing under them and they can't find a firm foothold, and the film sits you down in that emotional space and forces you to live in it. At the same time, the film is also funny - consistently laugh-out-loud funny, drawing reliable humour from well-drawn characters behaving in realistically stupid ways that we relate to too much.

I really did appreciate how much time the film gave to the adult characters. It's often very easy in stories like this for the adults to feel like side characters, much in the way that kids often see their parents as beings whose sole purpose is wrapped up in being their parent. But Benny Safdie and Rachel McAdams create fully developed characters with a genuine relationship together that feels like it's been strengthened through trials and challenges. Rachel McAdams in particular is as good as she's been in years, as a woman trying to find her place away from work, while Kathy Bates as the exuberant grandmother brings a lot of memorable high points to what would otherwise be a fairly minor character.

But ultimately the film does belong to Abby Ryder Fortson as the titular Margaret, and she is just delightful - whether in the way her face lights up whenever she sees the (socially unacceptable) boy she's secretly crushing on, or the way she's so relieved to find a group of friends that she allows herself to not notice the cruelty of the group's leader, or her joyous excitement at spending time with her grandmother, or the frustration she feels when she tried praying and God didn't fix the problem she was praying about. It's a sharp and convincing performance from someone who apparently has already built quite a career, and I hope her talent continues to develop.

It's just a wonderful movie, and I'm glad that I finally had a chance to connect to this material, albeit 35 years late.

So I had two possible choices for my Saturday night movie. I could have gone to see the new Wes Anderson film, Asteroid City, but I made a conscious decision not to see it because I know that it's getting a general release in the next few weeks, and I can see it then. Instead I decided to see this Argentinian film about a bank robbery, because I figured this would be my only chance to see the film.

I chose... poorly.

The film follows two colleagues working at a bank, Morán and Román. Morán steals hundreds of thousands of dollars from the bank, and only afterwards does he enlist Román to hold the money for him. Morán is resigned to spending several years in jail - in fact he voluntarily turns himself in - but he reasons the 3 1/2 years in jail will be worth it if he can come out and access the stolen money. But, between the ongoing investigation into the robbery being held at the bank and the general tension of having this money in your house, Román doesn't cope quite so well with the knowledge of holding all this money.

I should have paid attention when I saw that the runtime for this light-hearted crime heist film was three hours long. This is simply too long for this type of film, and just makes the film feel lethargic. Scenes play out much longer than they feel they need to, while the film makes use of the slowest dissolves in the history of cinema to transition from one scene to the next. But there is so much time wasted on irrelevancies - for instance, the opening scenes in the film revolve around a woman whose authorised signature at the bank is identical to that of an unrelated man. This feels so weirdly improbable that it must surely be a part of the plan for the bank robbery - but no, it has nothing to do with anything, and once a voicemail message is left for the second customer to contact the bank, it never comes up again. It's not part of the bank robbery, it's just something irrelevant we spent five minutes on.

And the bank robbery is hardly Ocean's 11. Part of Morán's job is to count the money in the vault and bring money out to the tills, so all he needs to do is sneak a bag into the box he uses to carry money in and out of the vault with, and that's your robbery done. It takes quite a bit of effort to make the most boring bank robbery in cinema history, but I think they achieve it here.

As the film carries on it just drags even more. Román decides he needs to get the money out of his house, so Morán suggest he go to some out-of-the-way town where there's a perfect hiding spot where no-one will ever find it. But while there, he happens to meet an aspiring filmmaker called Ramón, along with his girlfriend Morna, and her sister Norma, picnicking by a river, and suddenly we spend 20 minutes just with Román hanging out with these three for the day. And sure, Norma later does come to the city and have an affair with Roman - but we did not need to spend several minutes with them by the river playing a "name the city" game.

Part of the issue is that the lethargic tone also completely destroys any sense of the passage of time. Has it been a day or two since the bank robbery? Has it been several months? Has it been a year? I genuinely have no idea. This uncertainty is made worse when the film decides to squeeze much more event into a time period then there can possibly be. For example, the film initially seems to establish very clearly that there is only a couple of days between the robbery and Morán giving himself up - this seems clear by the fact that the bank's investigation into the robbery has only just started when word comes through of Morán's arrest. Except that much later we learn, in an extended 20 minute flashback, that there must have been several weeks between the robbery and the arrest, because after the robbery Morán also happened to meet Ramón, Morna, and Norma, and spent an extended amount of time with them - probably at least a few weeks - during which he too fell in love with Norma, in the kind of wildly improbable coincidence that you might be able to accept if you squint at it, but it really does feel like the film is putting its plotting (such as it is) ahead of credibility.

Then there's the illogical behaviour of the characters. Román goes to visit Morán in prison, which makes Morán angry because it draws attention to their connection - but also it's convenient that he came to visit because Morán desperately needs him to put $30,000 into someone's bank account or else Morán is going to be murdered in prison. Or there's the point where Román goes on a trip for several days, and calls in sick at work, but doesn't think to tell his girlfriend that he's going away, causing her to worry and called the bank, which then exposes the fact that he's doing something suspicious right at the point where he's under investigation because of the robbery. In what world does that behaviour make sense?

Now, it's entirely possible that there is some greater thematic richness to the film that I'm just not seeing. Perhaps the customers with the identical signatures and the anagram club of Morán / Román / Ramón / Morna / Norma all point to some bigger theme in the film. But if there is, I was so completely disengaged by the film that I just didn't care enough to want to find it. And the longer the film went on, the more I hated it.

One of these days, I will actually sit down and make a concerted effort to explore the works of the great Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. Prior to this, I'd only seen Tokyo Story, which really does deserve its legendary status. The interesting thing about the film festival's decision to screen The Munekata Sisters is that it's not a film I've heard people discuss as one of his best - I don't think it has the reputation of a film like Late Spring or Floating Weeds. But it's still a real delight.

The older of the two titular sisters, Setsuko, works to keep her bar afloat while in an unhappy marriage to an unemployed drunkard. She still harbours feelings for "the one that got away", Hiroshi, so when he returns to Japan after several years, the younger sister Mariko decides to try to push the two to reunite, although she also is secretly in love with Hiroshi.

So the film is a fascinating exploration about the changes in Japanese culture that occurred around the war. Setsuko is a product of the pre-war era, she's more traditional, wears a kimono, married young and feels obliged to stay married despite her unhappiness in the relationship. But Mariko came of age in the immediate post-war era, where the cultural structures were lessened, so she feels freer, she wears Western clothing, she wants to find her own path in life. And there's a constant conflict between the two sisters and their differing worldviews. In my favourite moment of the film, the two just sit and have a discussion about what it means to be old-fashioned and what it means to be up-to-date, about the timelessness of one versus the arbitrary nature of whatever is in fashion, about the constraints of one versus the freedom of the other. It's very much a moment where the central theme of the film is stated outright, but it's an intriguing discussion, well acted, and thoroughly engaging.

As for Ozu's direction, it's fascinating to watch. I enjoy how patient he is, frequently just pausing the action, letting everyone just take a breath. And I do love how fascinated he seems to be about people thinking - he's constantly bringing the camera in on a few moments of silence as the characters sit in a comfortable quiet, or lets the camera continue to run after the drama of a scene has played out, so that we can observe the characters processing whatever has just happened. It's difficult to put in words exactly why this is so enrapturing, but it brings a reality and a heart to the work that I loved.

It's not perfect - there's a very convenient death in the third act that manages to resolve a lot of the drama in a way I did find unsatisfying, and if this really is seen as lesser Ozu, then I suspect it's due partly to some of that convenient plotting. But it is a completely charming film, that did reinforce the need for me to address this significant blind spot.

To start, I should acknowledge that, due to my previous film overrunning, I unfortunately missed the first 10 minutes of the film. So when the end credits list the cast in order of appearance, and the first character credited is "Woman with Brush", I have no idea who that character was. Fortunately, this was not a film that left me feeling lost - within a couple of minutes, I just felt completely settled into the world of the film.

Hirayama is an ageing man working as a toilet cleaner in Tokyo. Every day he drives to visit all of the toilets on his round, taking great pride in his work to get them as clean as possible - he even uses a mirror to check the places he can't see. (His young work colleague doesn't understand the care he puts to the work, since the toilets will just get dirty again.) He takes lunch near a local shrine, where he takes abstract black and white photos of light shining through leaves, or he takes a freshly budding plant home to be cared for. He goes to the public baths. He very much has an attachment to the way things were - in the car he listens to Lou Reed or Van Morrison on cassette, while he carries a camera around with him to take photographs on film to capture any moments. He's extremely restrained and taciturn; his work colleague even jokes that he's never heard Hirayama speak. But then a collection of moments start to throw out his routine - his young colleague's girlfriend expresses an appreciation for his music; he finds the first move of a tic-tac-toe game hidden in a bathroom; his young niece comes to stay with him after running away from home.

There's something really satisfying about the film that is difficult to express. Perhaps, much like Hirayama's satisfaction at having done a good job, there's also a real satisfaction in watching a job be done well - even if that job is cleaning a toilet. Perhaps it's that Hirayama is a genuinely fascinating character, who is happy with the anonymity that comes with his job and who through his quietness really draws the audience in to learn more about him - and a late film hint about his background brings a real shading to his character. Perhaps it's just that he's a genuinely good-hearted person, giving money to his young colleague so that he can spend time with his girlfriend, or looking with concern for the homeless man who is always at this one park, just to make sure he's okay. Central to this is Koji Yakusho, whose work as Hirayama is just a delight. Because the character is so restrained, you have to look to the other clues that the character is giving you to their internal world, and he brings a real sense of joy and pride to the character.

I do find it intriguing when a film-maker decides to make a film that takes place in a culture outside their own, so I was interested to see German director Wim Wenders making a film in Japan. Could you make much the same film in Germany? Yes, perhaps But, without wanting to seem to applying stereotypes, I think the culture of restraint in that country is a big path of why Wenders choose to make this film there - a German version of Hirayama would have been very different. In any case, Wenders, working with Takuma Takasaki on the screenplay, has crafted a real gem here. They've created a character piece centred around a person who is instantly recognisable, and without any big or transformational moments, they slide the character ever so slowly towards change. It's a film that is extremely sweet, but never saccharine, and and that gives you as the viewer a genuine sense of uplift. I loved it.

A young waitress, Mikato, working at an inn at a small Japanese town, pauses for a moment to look at the river behind the inn, before going upstairs to clean a room with a colleague. But two minutes later, she suddenly finds herself back down at the river, and when she goes upstairs both she and her colleague know exactly what each other is going to say. When two minutes later she finds herself back at the river a third time, they realise everyone in this town is trapped in a time loop, and everyone in the town also knows it.

Two years ago, one of my favourite films of the festival was Beyond The Infinite Two Minutes, a science-fiction comedy about a television set that showed events from two minutes in the future. That film was the first film from director Junta Yamaguchi and the Europe Kikako theatre troupe, and now with their second film, this team is easily establishing itself as master of the inventive high-concept short-term time-travel comedy. While this film is perhaps not as technically impressive/insane as that earlier film (which presented itself as a single take, complete with pre-recorded recursions on the television set), they still take on the technical challenge of presenting each loop as its own single take - which is a challenging choice for a project as clearly low-budget as this.

It's a great example of how you don't need a big budget to make a great film; you just need a strong script. Here they have a solid premise for a film, but they also really think through the consequences of that premise and just how nightmarish that is. Think about Groundhog Day - yes, it must be awful to relive the same day over and over again, but a day is also enough time to do something; for instance, over enough loops it gives Bill Murray time to learn to play the piano. But imagine you're reliving the same two minutes over and over again. There's no time to go anywhere that's more than 100 metres away, there's no time to do anything. For some people it might be great, like the author who feels trapped by an impending deadline and suddenly realises he's freed from that obligation. But imagine being the people who were in the middle of eating a meal, and are suddenly faced with the prospect of only ever eating that meal for all eternity, never again getting to drink hot sake because there's no time to heat it. Imagine being the man who has already just reached the point where he's had enough of being in the bath, and suddenly finds that he's trapped in that bath for all eternity. I felt terrible for Mikato, who always has to start every loop running up stairs. Or there's the tension of realising that you're stuck forever in a room with someone you really do not like - fights break out, there's several (temporary) suicides, one person even resorts to killing the person they really cannot stand. For staff of the inn, they're always working without an opportunity for a break - and how exactly are they going to be paid for their work? And even if you're with people you like, you can't do anything - Mikato tries to go on a date with her boyfriend, watching a movie on a phone in two-minute chunks. Or when people in the town decide to gather for a meeting to work out what to do, they have to stretch the meeting out across multiple loops, and they always lose the first half of the loop because it takes everyone a minute to go from their starting positions back to the meeting room to pick up where they left off.

Now, to be clear, while I have highlighted the general horror of this premise, and the film definitely plays around with all of this, it's also a genuinely hilarious comedy. This is a fun, joyous film, filled with enjoyable characters, that loves how goofy this premise is and takes real delight in testing how wacky they can get. It's just a thoroughly enjoyable time. I was already interested in this team after their earlier film, and now I'm just completely sold on them.

A documentary about videography and its impact on our world, which takes its title from a comment by King Edward VII, who commissioned the film pioneer Georges Méliès to film his coronation in 1902. Méliès instead staged the coronation at his studio in France with actors, and when Edward saw the film he apparently marvelled "What a fantastic machine! It even filmed things that didn't happen!"

So here are some of the things that get discussed or shown in this film:

* Election night coverage

* Reaction videos to Game of Thrones

* The difference between what's in the frame and what's out of frame or behind the camera

* The way people will ride the limits of acceptable sexualisation in their TikTok videos

* The way people will use their TikTok following to draw paying customers to their adult content on OnlyFans

* How-To videos, showing everything from how to save yourself if you fall through ice, or how to make a homemade bomb, or how to defrost your freezer

* Leni Reifenstahl talking in the 90s with pride about the techniques she used to film Hitler and the Nazis for Triumph of the Will

* Daredevils filming themselves in extreme situations

* Ted Turner taking pride in his channel showing The Beverly Hillbillies reruns because people want a break from the news

* Ted Turner founding the 24-hour news channel with CNN

* Political propaganda

* The use of the Netflix algorithm to push people towards watching Adam Sandler films rather than Schindler's List

* The psychological analysis used to develop TV programmes that will capture an audience to whom advertisers can sell Coca-Cola

* People livestreaming themselves sleeping

* People calling the police on livestreamers as a joke

* The difference between our personalities speaking to a camera vs speaking to someone in person

And it goes on - the Voyager satellite, January 6, and on, and on...

And if that seems like just a long list of stuff, that's pretty much how the film felt. It's under 90 minutes long, which is much too short to cover all of this material. And so the film just takes a scattergun, hit-and-run approach to the material. No sooner have you heard about one issue when the film moves on to another matter. And if you ever pause to actually think about anything that the film is saying, you'll wind up five or six issues behind the film. The film is in a constant race against itself to squeeze everything in - oh my gosh this is terrible look at that that is so cool oh damn that is just so fucked up look a puppy that's cute but it has no legs that makes me sad...

There's so much squeezed into the film that it never has a chance to develop any significant thought or a coherent thesis. If I had to summarise this film, it would probably be that the way we in this society film our entire lives is probably bad ... except for the ways it's good, and in those circumstances it's a good thing ... but it's mostly a bad thing ... ish.

It's just all over the place. It's an enjoyable film, in the way that it would be fun for someone to curate a YouTube feed for you, giving you just the best videos available, but I suspected that's not what the filmmakers were trying to achieve. And that's a problem.

Even as I bought my ticket for this film, I was dreading seeing it. I'd heard it was a really good film, which was why I was going to see it. At the same time, I'm someone who cannot stand the thought of watching Dr Pimple Popper, so the prospect of seeing a two-hour documentary filled with graphic scenes of surgery really did not appeal to me. But I made a decision for myself - I will not look away from this film. No matter what they show I will not look away. Even if they show eye stuff (shudder) I will not look away.

Filmed over a number of years in Paris hospitals, the film is a portrait of the intense amount of effort that goes into keeping a person functioning. There's no commentary to the film; our only context for anything we watch are the conversations that the medical staff have with each other about what they are doing at the moment. So we will spend several minutes watching something being cut from a person's body, and it's not until we hear the doctor express surprise at the size of the prostate that we realise what we've been looking at. There's a moment where some medical staff are examining a large piece of flesh - for some reason it actually looks on one side like a well-done steak, all charred and blackened - and the staff have a ruler to measure the size of the tumor, and it's not until they turn this pound of flesh over and you'll see the nipple that you realise this is someone's breast removed in a mastectomy. But the film is not just about the efforts that go into keeping our bodies functioning - we also rely on functioning minds, which is why some of the hardest footage to watch are the moments with dementia patients, who seem to barely have any understanding where they are and who become fixated on different things.

For the most part, I was surprised to realise I didn't find the surgical scenes too difficult to watch. A big part of that, I think, is the fact that so much of the footage was shot using microscopic cameras, where every little detail is so blown up that it becomes impossible to actually connect anything I see on screen with any form of recognisable viscera. It was much harder to watch when the body parts were recognisable. There was the dreaded eye stuff (shudder), with an operation to replace the lens in the patient's eye. Or there was a man's penis, with a massive tube inserted up his urethra.

And in the film's most memorable and enthralling moment, we watch as an emergency caesarean is performed, with the entire process, from first incision to the nurse checking the baby in the neonatal unit, presented in a single shot. When they take the scalpel and cut open the mother, it's fast, it seems almost easy - just three quick slices with the scalpel and she's cut open. When they make those cuts, the human body just seems so frail, so easy to damage. But then it takes two people, each pulling with all their might with both hands, to open the mother up to free the baby. And you see the effort involved to pull her open, and it just seems as though there's so much strength in the body. And then you see this impossibly tiny human being, and the whole process just seems miraculous. And I think that's essentially the thesis of the film - the miracle of human existence and the simultaneous fragility and strength of the human body.

At the same time, we are reminded that there are people doing all these things, and they are working within a human system - for both the good and the bad that that means. We hear a doctor complaining about overworking and his team being understaffed. Or they complain about not having the resources they need. At one point we witness a surgery potentially going disastrously wrong with unexpected blood in the wound, but someone dropped the only suction tube onto the floor and now there's a question about whether the excess blood can be cleared up.

The footage presented in this film is simply extraordinary. It really is a film that makes a massive impact. It's not an easy film to watch, but I would recommend it.

Full disclosure: I missed the first 5 or 10 minutes of this film after stupidly going to the wrong cinema. But I rushed and made it to the correct cinema without missing too much, and I was glad I did because I really liked this documentary.

The "utopia" of the title is North Korea; at one point in the film, a defector from North Korea comments that everyone in that country is taught that their country is a utopia and that everywhere in the world is worse than where they are. The film is essentially broken up into three interweaving strands. In the first, we get a basic history of the creation of North Korea (I'd always thought the country division was a consequence of the Korean War, but apparently they were divided much earlier, and the war happened because the North invaded the South; I am very bad at history), along with stories from various defectors about the realities of life in North Korea. The second follows Pastor Seungeun Kim, who has apparently helped 1000 people defect, as he helps a family of five (including both a grandmother and young children) escape to safety after they cross the border into China. And the third follows Soyeon Lee, a defector who struggles to get word about her son after he is caught trying to cross the river into China.

The material about North Korea as a country is very interesting, if presented as fairly standard documentary fare. We get some light insight into how North Korea came to be, how the Kim family came into power, and how and why the initial success of North Korea declined to the failure of today. We get a number of talking heads from different defectors talking about their own experiences, and no matter how often you hear stories about life in North Korea, it never fails to astonish - whether it be the story of the white-gloved inspectors making surprise checks to ensure each family's portraits of Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong Un have been adequately dusted, or the way people have to collect their own feces and give them to the government to be used as fertiliser, or the strength of anti-American propaganda (so strong that the grandmother expresses fear that, while the documentary makers seem nice, they might turn evil at any moment), or the fact that North Korea borrowed elements from the Nativity to be part of the story of the birth of Kim Il-Sung, who is literally revered as a deity!

The most dynamic and engaging part of the film is certainly the part following Pastor Kim in his efforts to rescue this family. When we hear stories about people defecting, it often seems like it's surely not that difficult - just find a place where you can cross the border into a different country without being seen. But watching this film, it seems a miracle that anyone ever manages to defect. The direct border between North and South Korea is impassible, so the only option is to cross into China, and then from there travel to Vietnam, and then to Laos, all of which are communist countries with good relationships with North Korea that will send defectors back if they are caught. Only once they've travelled thousands of miles, and have reached Thailand, can they be said to have escaped. Meanwhile, Pastor Kim uses funding provided by his church to make bribe payments to officials to look the other way, or make payments to mercenary "brokers" who help people escape but who do so out of financial considerations - and since China will also put up significant rewards for anyone helping apprehend defectors, there is always the risk that the brokers will see more financial benefit to handing the family over for a reward. Or perhaps the brokers might make more money if they sell the defectors into sex slavery or harvest their organs. Or there's the chance that brokers might suddenly extort more money by refusing to take them any further without further payment. And meanwhile the trip is insanely risky, having to deal with the famously massive surveillance system in China, or the need to cross three mountains in the jungle in the middle of the night, or avoid checkpoints, or take a perilous river trip that could kill them when the freedom of Thailand is literally in sight. There's genuine suspense and tension in these scenes - even if we assume that the family is going to make it, it just feels like they are doing something impossible.

Unfortunately, the one part of the film that didn't work for me was Soyeon Lee's story. And that's a shame, because in a lot of ways it's the most urgent part of the story - what happens to people who are caught trying to defect. The problem is that inevitably there's just not enough information to know what's going on - we are left with Lee sitting in South Korea talking on the telephone to a third-party broker who is passing on messages about the situation with her son after he is caught. No-one really knows entirely what happened - they are not even sure he was actually trying to defect, since there is a suggestion he may have just been trying to get his mother to return to North Korea. No-one knows what will happen to her son, whether he will be sent to prison, to work camp, or to a concentration camp, whether he'll be able to be released in a few years or whether he'll be held for the rest of his life, what torture he'll undergo, whether he'll be killed. And it is devastating for her as a mother to go through that, and it's important to explore that. But as a movie, it's very hard to make that material work cinematically, especially when contrasted with the excitement and suspense of the defector family and their long trek to Thailand and freedom, and so every time we return to Lee the film feels like it loses energy. I'm not sure how you resolve that issue, because this is important material that needed to be in the film, but the way it's presented here simply didn't work for me.

But on the whole, it's a fascinating, disturbing, and challenging documentary. It may not all work, but it is a significant film. A few years ago, there was an excellent documentary in the festival called Under the Sun, which was a horrific portrait of life in North Korea and the two films would make a perfect if disturbing pairing. Both of these films are worth seeking out.

Leon is a young author struggling with his newest book. Needing to get away to finish the novel before his publisher visits to discuss it, he accepts an invitation from his friend Felix for the two of them to go to his family's holiday home. What they didn't realise until they arrived is that there's already a young woman named Nadja living there.

Director Christian Petzold has become a strange figure for me. Over the past few years, I've taken to watching his new films every time one appears in the festival, and there's always something in each of his films that bothers me, that I couldn't get past, yet there's something about him I can't put my finger on that keeps pulling me back to his work. Here, the thing that really didn't work for me was unfortunately the main character. Leon is not a nasty character, but he is unpleasant to be around. He's sullen, moody, irritable, bad-tempered, I don't know that he smiles even once - a lot of his behaviour frankly reminded me of a teenager taken on a family holiday he resented going on. Now, some of that behaviour might be justified, or at least explained, by his insecurity over whether his new novel is actually coming together, but I found very little indication about what would make Felix want to spend any time with Leon, much less go away to a holiday home with him. He also shows no sign of having any interest in anyone else - there's a late film revelation about another character where the audience is well ahead of Leon in figuring this information out, because he seems to have just ignored very obvious signs. So when this film is about someone whose presence you just do not enjoy, that's a problem.

Then there's the point where he confesses his love for Nadja, which just made me wonder when this actually happened. He claims he fell in love with her the first time he saw her, but if so this sense of being overwhelmed was completely invisible to me. Every interaction between the two feels so completely marked by an annoyance at having to deal with her that I just could not accept the notion of his love - are we intended to view him as a 10-year-old showing his affection for a girl by dunking her pigtail in the inkwell. It's as though we are supposed to just assume, because these are the lead male and female roles, that of course they'll fall in love. The film ends on a moment where Nadja smiles at Leon, and I struggled to identify anything in their previous interactions that would justify such a warm reaction, as opposed to maybe a minor nod of acknowledgement or something similar.

But also I have a real problem with the entire writing on the film. I just don't know that I believed that anyone had any existence outside of the film. Beyond Leon's irritability, I would struggle to identify anything that distinguishes any of the characters in the film. They seem to exist solely to be present and fulfil a plot purpose, without having any sense of an internal life. And then there are the points where people just behave in a way that I could not recognise - for instance, if you were staying in an area that was dealing with a major problem of wildfires, and you had no form of transportation, I feel you would take deliberate steps to protect yourself, as opposed to doing what they do here, which is just rely on whatever the typical wind patterns are in the area. It's just so bafflingly unconvincing.

And yet ... and yet, I enjoyed watching the film, even as I was really bothered by it. And that's the contradiction I keep coming to with Petzold - there's something in there that works, even if the film is a whole does not, and it keeps pulling at me. Give it another two years, and there will be another Petzold film, and I'll go and see it hoping that this will be the one that works for me, and it will not be, and it will disappoint me. Apparently I'm fine with that.

This one I loved. I couldn't say I enjoyed it, but my gosh I loved it.

Lea is a 17 year old girl living in a small California town with nothing to do in her summer holiday. She fights with her single-mother, she sunbathes with her best friend, she has bad sex in the back of a car with someone else's boyfriend, she drinks beer and watches movies with her group of friends. And then one day, she sees this older guy, a 34-year-old named Tom, and there's almost an instant spark between them. She's wary, but he pursues her, and he's sweet, charming, and loving, and she decides she feels safe to start a relationship with him. After all, he would clearly never do anything to harm or exploit her.

The most obvious thing I appreciated about the film was its patience. It's a really long time before we really get any indication that there's anything negative going on at all - so much so that I was starting to wonder whether I was watching a film that is actually positive about this type of relationship. She feels so alone, her mother is busy with her various boyfriends and doesn't have time for her, her friends aren't great but in this small town there's not much choice - and then she meets this guy who actually loves her, who actually cares about her, who makes her feel valued and wanted. And then, when we do starts to see the warning signs of how bad Tom is, it's always surrounded with plenty of affirmation. It feels as though he's just testing the waters - if I say this, does it scare her away - but he'll let those moments pass by so quickly and covers the bitterness with so much sugar that she just accepts it, until she's pulled down. There's a practised confidence in him, you can see that he's done this before, he knows how to recognise when an opportunity arises for him to drop a little seed to push her in a particular direction. It's fascinating to watch just how easy it is for someone to be manipulated by a person who knows what he's doing. Looking the film up after the screening, I discovered that the writer/director Jamie Dack based the film on her own experiences as a teenager in a relationship with a much older man, the way at the time everything seemed normal and natural, and how it was only with hindsight that she could see how twisted that relationship was and how he had groomed her. It sounds like things never went as bad for her as they did for Lea in the film, and I'm glad about that for her, but the film does have a great deal of insight into this behaviour, how a seemingly smart person could be seduced in this way, and it really does have the ring of authenticity. One of my favourite touches in the film was the understanding of how patterns can recur, often across generations, and how we are often better able to get perspective about other people than ourselves - there's a great moment early on where Lea gets angry at her mother for doing something unwise, which makes it particularly devastating later in the film when Lea makes exactly the same choice.

Lily McInerny's performance as Lea will be one of my highlights of the festival. This is apparently her first role, and I just can't comprehend how you get that performance out of a first-time actor. A lot of the performance is certainly typical angst-ridden teenage girl, and she is great in those moments, but you could find so many people to play that role. But then the turn happens, and she goes through the worst experience she can imagine, and she gives such an astonishing, nuanced, subtle performance of someone trying to process her trauma, that it just astonished me. On the other hand, there's Jonathan Tucker as Tom. Tucker is definitely one of those people you recognise from somewhere - for me I think it was probably from his recurring roles in Parenthood and Justified - and he's just perfect here. Achieving that delicate balance where he comes across as convincingly sweet and safe while retaining enough of the air of danger that his turn makes sense must be tricky, but he pulls it off expertly.

I also appreciated the convincing sense of a location and the community around these central characters. Having just come out of Afire, which so bothered me because of its shallow characterisation, I was really impressed by how richly developed the world and its people actually were here. Within a matter of minutes, I felt I understood this world, picked up on the barest of hints about relationships that ultimately proved true, and could predict how Lea would react to certain situations. It's all reflective of the care that Dack took both in perfectly creating this world in her script, and creating it on camera. I particularly appreciated the nuances in the relationship between Leah and her mother - you can see how a typical temperamental teen would feel hurt in how they interact, even as the mother (Gretchen Mol is great in the role) can't quite comprehend how her daughter could have misunderstood their fundamental relationship.

As I say, this is not a film that you are supposed to enjoy, but I did walk out of it feeling genuinely excited as a film fan. Between Dack and McInerny, it feels like we've been introduced to some real talents, and I'll be interested to see where they go.

(Also, it's worth noting that this is an expansion of a short film that Dack made back in 2018. The short is excellent and also worth watching.)

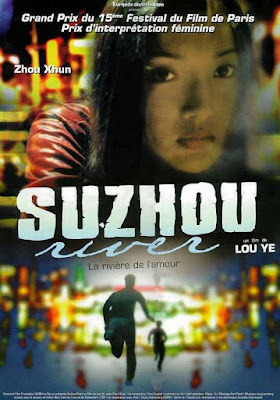

I had never heard of this Chinese romantic mystery drama, made in 2000 by writer/director Lou Ye, until it appeared in the Classic strand in the festival programme.

A videographer is hired by a local bar to film their mermaid act for a promotional video; he and the "mermaid" Meimei then become lovers, but she's unreliable and often vanishes for days at a time. One night, she asks him whether, if she ever vanished, he would hunt for her "the way Mardar searched for Moudan". We then hear the story of Mardar's love for Moudan, as told to the videographer, mostly by his girlfriend but also partly by Mardar himself - how Mardar was a motorcycle courier who fell in love with Moudan, the daughter of a wealthy businessman, and how he was then pressured by criminal contacts to hold Moudan hostage, which ends badly. Years later, Mardar decides he needs to hunt to find his beloved Moudan, and when he comes across Meimei he's convinced he's found her, since she does look identical to the missing Moudan.

So you might have already noticed the odd thing about the film. There is this framing device, about the unnamed videographer and his girlfriend Meimei, told from the perspective of the videographer, but much of the film is a flashback - except that it's a flashback of a story that's the videographer was for the most part not present for. He heard the story from Meimei, who might have been present for the story, depending on whether she is the vanished Moudan (and the film does answer that question) - but this means that we are watching the story at best secondhand, possibly thirdhand. This feels like an odd construction for the film.

The film also adopts this very hand-held filming style, which was unfortunate because my seats were very close to the screen, and all of the shaking made me feel almost queasy - I was glad it was only 80 minutes. But it very quickly becomes clear that this film style is intended to replicate the point-of-view of the videographer - we are seeing the world through his eyes. That is, until we start the story of Mardar, since the videographer was largely not present for those events. But the shaky camera work remains, even though it makes little sense - whose point of view are we adopting when we are sitting behind the television looking at Mardar and Moudan, and if the answer is no-one's, then why is it still so shaky? But the failure to clearly delineate the filming style between the scenes in the videographer's point-of-view and the scenes that were not became actively obstructive at times. The film transitions from one to the other at several points through the story, and it felt disorienting, because it would always take a few moments to identify when a transition had occurred. And that does become a barrier to clear storytelling.

I was also intrigued to notice that the film seemed to be taking inspiration from Vertigo - both are romantic mysteries, both revolve around a man who is haunted by the loss of the woman he loves, both involve a person who is identical to the lost woman, both prominently feature scenes where a person changes their hair colour (albeit here it's by wearing a wig rather than using hair dye), both feature multiple deaths by falling (albeit from a bridge rather than a building or a tower), both feature scenes where a man dives into the water after a woman tries to kill herself, both feature a significant time jump. Now, this similarity probably would have completely slipped past me were it not for the fact that the musical score has a particular phrase, repeated at several points throughout the film, which unmistakeably (if briefly) quotes from Bernard Herrmann's score. But I did find myself wondering what the purpose of this was. The film is not a remake - while there are these elements that are so closely similar to the Hitchcock, the story as a whole and its concerns are very different - but then this question nags at me; why draw a connection between the films by quoting from it?

Ultimately, I think I just found this one somewhat unsatisfying. It's perfectly enjoyable to watch, but it feels hollow, and I don't know that I really connected to what I was trying to express. So that's a disappointment.

The night before his wedding, Shunsuke find himself at a surprise party organised by his workmates. After drinking too much, he sets off walking, somewhat unsteady on his feet. When he wakes up, he find he has fallen down an open manhole, and the rusty ladder has broken away. He tries calling all of his friends, but the only person who even answers this late at night is an ex-girlfriend, and he's not sure if she's being as helpful as she claims. He also (somewhat reluctantly) calls the police. But for some reason the GPS on his phone is giving him entirely incorrect location information, so he can't guide anyone to where he is. Then he has an idea - he creates a social media identity of "Manhole Girl" (because people help girls), calling for people to help him work out where he is and come to rescue him. But eventually, when it is realised the manhole is located somewhere he could never have walked to, it becomes clear that this was no accident and he has been abducted. And this revelation leads some people to take on the idea of rescuing Manhole Girl and seeking justice for her.

So for 80 percent of the film, I was really enjoying the experience. It's light, funny, extremely suspenseful. You can see Shunsuke doing some smart things, and even when he does do something stupid there's at least an understandable reason for doing so - for instance, it's extremely stupid to try throwing your phone up out of the manhole and having it fall back down to you, because there's an obvious risk of losing your only means of communication, but at the same time it's understandable as a desperate effort to get some information about the location outside. At times it's appropriately gory - the scene where he uses an office stapler to staple up his wounds is rather fun. And it's often very unbelievable, whether it be his body's weird ability to survive so many brutal falls, or the fact that he somehow survives an explosion(!) in the manhole seemingly without a scratch.

And while the satire of social media is certainly broad, it's sadly not unbelievable, with the portrayal of weaponised internet fully on display - there is this terrifying point where Manhole Girl's followers, for no real reason, become convinced that one of Shunsuke's colleagues is the abductor, and it all builds and escalates until before long someone is torturing this innocent party to find out where he is keeping Manhole Girl. But at the same time, there is something smart about utilising the entire specialised knowledge of everyone on the internet to solve a mystery, so suddenly details like the particular sound of a train can become vital clues, because there is someone out there who can use that information to narrow down the location.

So most of the film is really a very strong entertainment.

And then the third act happens.

I had been convinced through all the film that Shunsuke was dead - it would explain so much, from the weird dreamlike tone immediately before he fell in the hole, to his body's ability to survive brutal punishment. And that would have been a bad reveal. But no, the explanation is so much worse then that. Now, while I will try to talk around exactly what happens, there will certainly be hints at spoilers following.

So it turns out that it is not only not a mistake that he fell into the manhole, it is also not a mistake that he fell into THIS manhole. It is revealed that he has a secret that is connected specifically with this manhole. In fact, his secret is so strong and so connected to this location that I found it unbelievable that he didn't immediately guess where he was - as soon as he found himself in a manhole, he should have thought "this could be connected to that thing that happened", at least as a possible starting point.

But also, the film has a real challenge in the identity of the antagonist. Because Shunsuke finds himself in the manhole so quickly, and we don't leave the manhole to get any external viewpoint, the abductor could be anyone, because there is no-one we feel we really know enough for it to be satisfying that they are the abductor. Pick a person out of a hat, and I would feel no greater connection to the revelation than if it was anyone else. But now I'm left with a bunch of questions - how did the abductor come to be in possession of certain information, and having discovered this information why did they choose this particular response? Also, why give Shunsuke a phone when it is so clear that connection to the outside world through the internet is a threat to their plan? And what on earth was motivating their final actions?

Look, even in as terrible an ending as this, there was some genuine enjoyment, with the audience laughing allowed and reacting as a group to particular moments. But this ending took so much goodwill from the film and destroyed it. And that is a disappointment.

Jennifer Connelly plays Lucy, a narcissistic, self-involved former actress who decides to go on a week-long spiritual retreat to try to find herself, and who is annoyed to find the retreat has been invaded by a famed model who is emblematic of all the worst things she sees in herself. Lucy barely ever speaks to her daughter Dylan (played by writer-director Alice Englert), working in New Zealand doing stunts for a clichéd fantasy film, although the mother and daughter are technically not estranged. But an unexpected injury causes Lucy to leave the retreat early and Dylan to travel to reunite with her.

So the film is an enjoyable work. Englert has a nice comedic sensibility that had the audience laughing hard constantly. At times there's just a gleeful absurdity - in reality, the woman explaining the importance of having no technology at the spiritual retreat would probably not be standing next to a person playing a zombie-killing game on a computer, but it was a funny joke. At other points, there's some nice character-based comedy - Lucy hilariously somehow manages to order breakfast in possibly the most inconvenient way imaginable. And sometimes there's just a shocked laughter, where the film flings you into a space you never imagined it going and there's only one way to respond.

The performances in the film are a real highlight. Connelly is a lot of fun playing a sharp-tongued toxic character who is consumed with resentment towards all around her. Englert is fascinating as a person who seemingly has gone into stunt work as a way to avoid dealing with the issues she's struggling with, largely because it offers her an opportunity to self-harm without actually self-harming. And while he is really only in the first half of the film, Ben Whishaw is hilarious as the retreat guru, a man who has been seduced by the lure of comfort and reward away from the ideas he's espousing, and who is not above manipulating circumstances to connect with a supermodel.

Where I struggle with the film is that its message feels rather shallow and obvious. It's hardly a new target for satire to set a story at a spiritual retreat, and that is a lot of fun. There is this running idea in the film that these people are actually using the retreat to feel as though they are taking steps to improve themselves without ever fully buying into the experience - indeed, it seems Lucy has been on many such retreats before, but is still the exact same person she always was. But while it is a very enjoyable part of the film, I was starting to feel that we we were starting to hit the same beat over and over again, and so it was a surprising but gratifying development when the film takes a turn away from that setting. But the ultimate revelation that seems to come to the characters - that hiding yourself away in a place where all your thoughts are indulged as self-actualisation may not actually be the answer to solving your own self-involvement, and that if you want to better connect with someone then actually connecting with them might be a good start - doesn't really feel like that profound a statement.

So while the film is a lot of fun, and I would absolutely recommend at as an enjoyable time at the movies, it does feel as though Englert is perhaps struggling to find a clear vision or point of view for the film. Still, she's a talented filmmaker, and I'm certainly interested to see where she goes.

(And one last thing - it's a very small point, but if I was the San Francisco International Airport, I would probably be a little offended that they tried using the Wellington domestic baggage claim as a stand-in for them - that does not look like any international baggage claim I've never seen. And it's so unnecessary also - they really didn't need to draw attention to it; we already know the character is flying to the US, so they could have just not put up that sign, and we would have assumed it was a connecting flight at any generic airport.)

Julianne Moore is Gracie, a woman who was the subject of a national scandal after she, as a married woman in her 30s, had an affair with a 13-year-old boy, Joe, and gave birth to his child while in prison. Twenty years later, the two are married, and the scandal largely seems to have been forgotten - they are much loved members of their community, with only the occasional package of excrement sent to them as a reminder of that time. But now a film is going to be made about their story, with major star Elizabeth Berry (played by Natalie Portman) playing the lead role, and so she comes to spend time meeting Gracie, as well as everyone else who was around at the time of the scandal, in an effort to try to understand the character.

Very obviously drawing inspiration from the case of Mary Kay Letourneau, director Todd Haynes seems fascinated by what might have driven this woman into this shocking action. He also seems intrigued by the current wave of public enthusiasm for prestige true crime - the successor to the trashy TV movie that once filled our screens. There's a particularly amusing moment where we watch one such trashy adaptation of Gracie's story, and we can understand why she would be looking to this prestige adaptation as an opportunity to reframe her story. But there's a moment in the film that truly drives home just how shocking Gracie's crime was. Elizabeth watches several audition videos from various 13-year-old boys looking to play the part of Joe. Eventually she phones the film's producers and asks for them to expand the search. After all, they need Joe to be stronger, more confident, sexier. And when we eventually see the actor cast for the role of Joe, he's quite noticeably older than the 13-year-old that Joe was. The fact is, the only way to see a 13-year-old as anything other than a child is to be completely delusional. Julianne Moore picks this up - she feels genuinely damaged in her performance, someone who's putting all her efforts into putting on a public face of strength, confidence, and certainty, convinced that if only people heard her story as it truly was then they would understand her actions, and maintaining a clear lie that she was seduced, because it's the only way that she can cope with the damage she has caused. And the film definitely hints at psychological damage from her youth that may have influenced her actions. It's a clear comment on the way patterns of behaviour are learned and influence us long into adulthood.

But if the crime that Gracie committed was so horrific, then what are we to make of the decision to make a movie of it? At one point, Elizabeth finds herself talking about the experience of filming a sex scene, the way the bodies move and interact and how easy is for emotional lines to be crossed. It's a telling moment, because we are reminded that this project that she's working on will definitely involve moments that will risk such emotional line-blurring with another young child. It's a fantastic performance by Natalie Portman, partly because it's for the most part almost on the periphery. She's always present, but very rarely herself. Her reason for being in this place is to observe and learn, and so much of her time on screen is spent just watching, asking questions, maybe occasionally rehearsing a posture - until we get to the best scene in the film, a moment where she stands in front of a mirror and for the first time performs as Gracie, all the mannerisms, all the vocal notes, and it feels like Gracie is in the room.

Charles Melton, as the now-thirty-something Joe, also gives a fascinating performance. He feels like a person who simultaneously grew up too soon and also never grew up at all. Having been thrust into adulthood at such a young age, complete with the responsibilities of being a parent while still a child himself, he never had the chance to grow into that role, and so he feels like someone who is constantly yearning for a lost childhood. And much in the same way that Gracie puts on a different face for public and private, so does Joe - in public he's a mature and thoughtful father and husband, but in private his entire physicality seems to shift, and he seems to revert back to being a 13-year-old having to support this woman who might as well be a mother to him. It's as though this experience has trapped him in a toxic codependent relationship from which at just seems impossible to escape.

If I had to make a criticism of the film, I am genuinely battled by the music. It's essentially an adaptation of Michel Legrand's main theme for the 1971 film The Go-Between, but while (from very vague memory) it's effective in that film, the way it's deployed here is utterly baffling. The heavy-handed, ominous piano notes are frequently at odds with the film, and their repetitive deployment make moments as seemingly inconsequential as "We need more hot dogs for the grill" into a moment of literally laughable terror. I do not think it's an accident - as a pre-existing piece of music, Todd Haynes knew the piece in advance and will have known exactly what he was going for when he chose to deploy it. But it just feels so out of place that I cannot imagine what he was going for.

That said, the film around the music is fantastic, an intriguing exploration of the way true crime and the media can create abstractions out of real people and real victims, and the consequences of being involved in genuinely terrible crimes. I really did like it.

Part of the Classic strand in the festival programme, Chocolat was the directorial debut film for a young Claire Denis back in 1988. The film focuses on a young French girl, named France, living with her parents in Cameroon where her father is working as an administrator. France has a particularly close friendship with one of the main servants, Protée, who also has a definite air of mutual attraction between him and France's mother. And all this tension comes to erupt when a small plane crashlands nearby, and the passengers have to stay with the family for several weeks until they can leave.

It's very much a strong debut for Denis - but it does feel like a debut film. Denis already has an extreme confidence behind the camera and a very clear sense of artistic identity - she's a filmmaker of great patience and dramatic subtlety, and I'm always going to love someone who just positions the camera and then lets an entire scene play out in front of it. There are moments where you find your eyes exploring the frame, noting how this element or that interacts with a previous scene or sets up subsequent events, and it's always a delight.

She also draws fantastic performances from her cast of actors. Working with a young inexperienced actress like Cécile Ducasse (playing France in her only film role) must have been a challenge for a new director, but Denis brings out a natural ease to the performance that is a delight. Isaach de Bankolé is one of those actors I'm always happy to see, and it's fascinating to watch him in his youth playing the essential role of Protée - he's a character who speaks rarely, but there's real strength and character communicated through the way he carries himself or the expressiveness of his face that is just wonderful to watch.

But where the film does reveal itself as a debut film is in its heavyhandedness in exploring its themes. It's quite plainly about colonialism, about white attitudes towards black people, and almost every scene in some way feeds into that idea. There's the fact that France's father is an "administrator" helping to run the country on behalf of a foreign power, while the people who are actually native to that country are largely present as servants. There's the fact that the white family gets to have indoor showers, while the black servants must shower with a pail of water outside, only just barely hidden from public view as long as the showering person doesn't step too far away from the wall. There is the African cook who is constantly demeaned for the poor quality of his coffee or his inability to cook food in the proper French way, despite the many cookbooks available - ignoring the fact that he can't read. When the white passengers of the plane needs to have the ground levelled to create a runway to take off, it's the black people who have to do this backbreaking work. Or there's just the way the French casually talk about this place they've come to as "our country" in front of people who have lived here their entire lives. And to be clear, the film is making solid arguments. But I do wish that some of Denis' subtlety in the dramatic sphere was also reflected in her thematic approach.

Still, it's a strong film, and even this early you can see the potential in her work that would lead to her becoming a significant voice in the film world. I really enjoyed it.

Anselm Kiefer is apparently one of the most significant artistic figures working in Germany today, and this film serves as a representation of his work and also as a meditation on the philosophy of the artist himself.